At The Regent

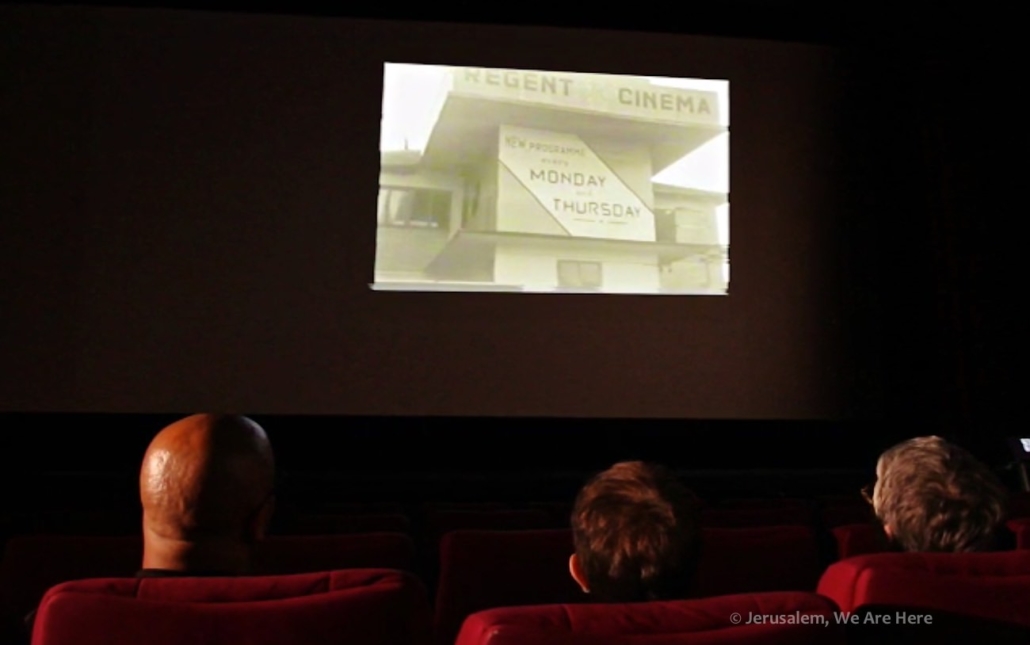

Two heads, one bald, one full-hair, are peeking out from above the red velvet chairs. Their owners, Anwar Ben Badis and Mona Hajjar Halaby, who conduct the Arabic and English tours, respectively, of the Jerusalem, We Are Here (JWRH) interactive documentary, are exchanging family memories of the place. Dorit Naaman, the creator and director, joins them as up on the big screen fragments of an old reel start rolling.

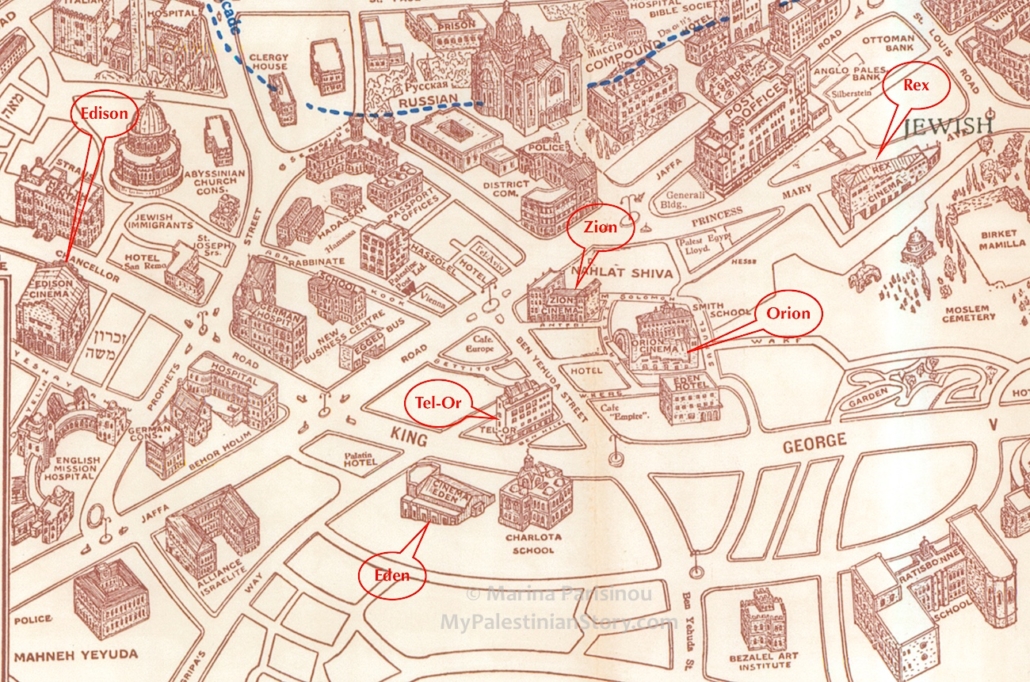

It’s July 2015 and we are filming the opening shots of JWRH at the Regent, the longest-running cinema in Jerusalem. Today it has a different name, but to us, as we go about remapping this area and bringing back, albeit digitally, the people and the life that existed here till 1948, it is and always will be the Regent.

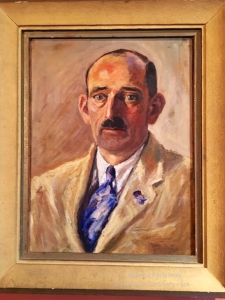

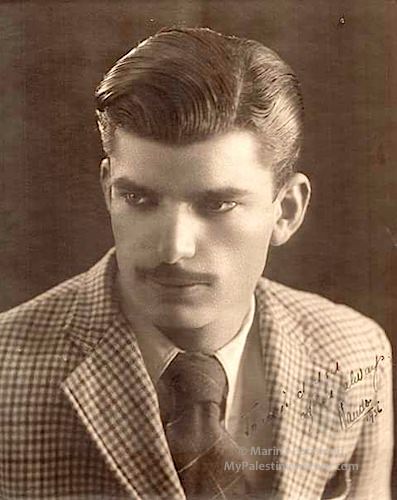

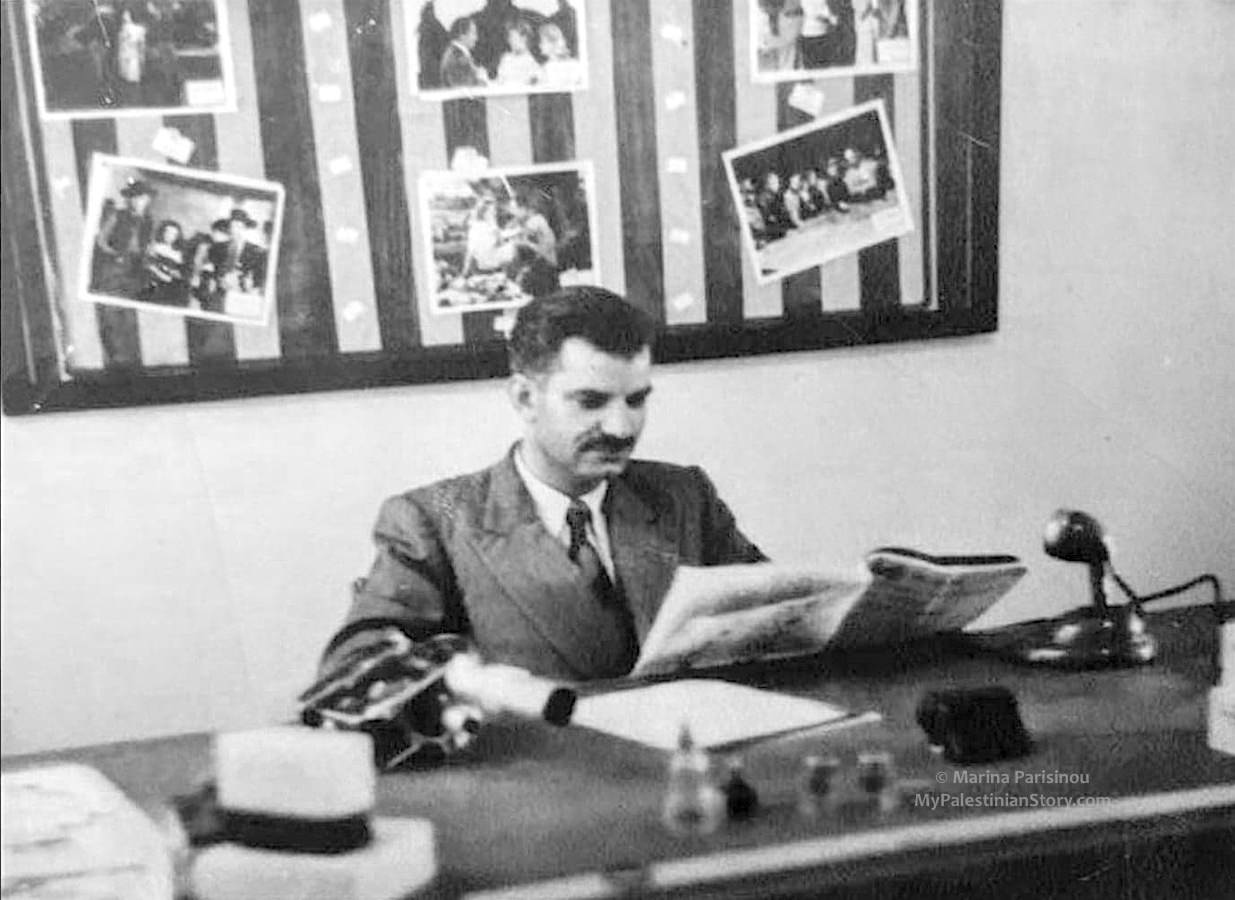

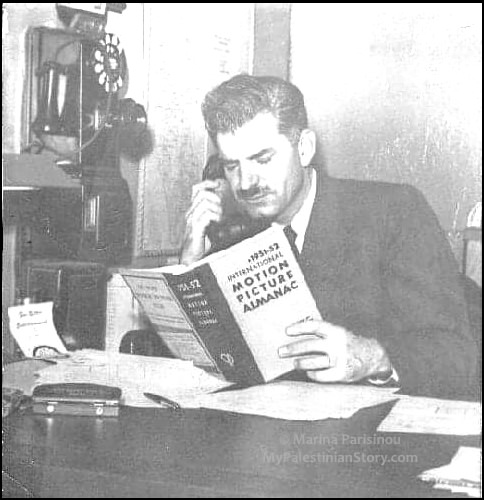

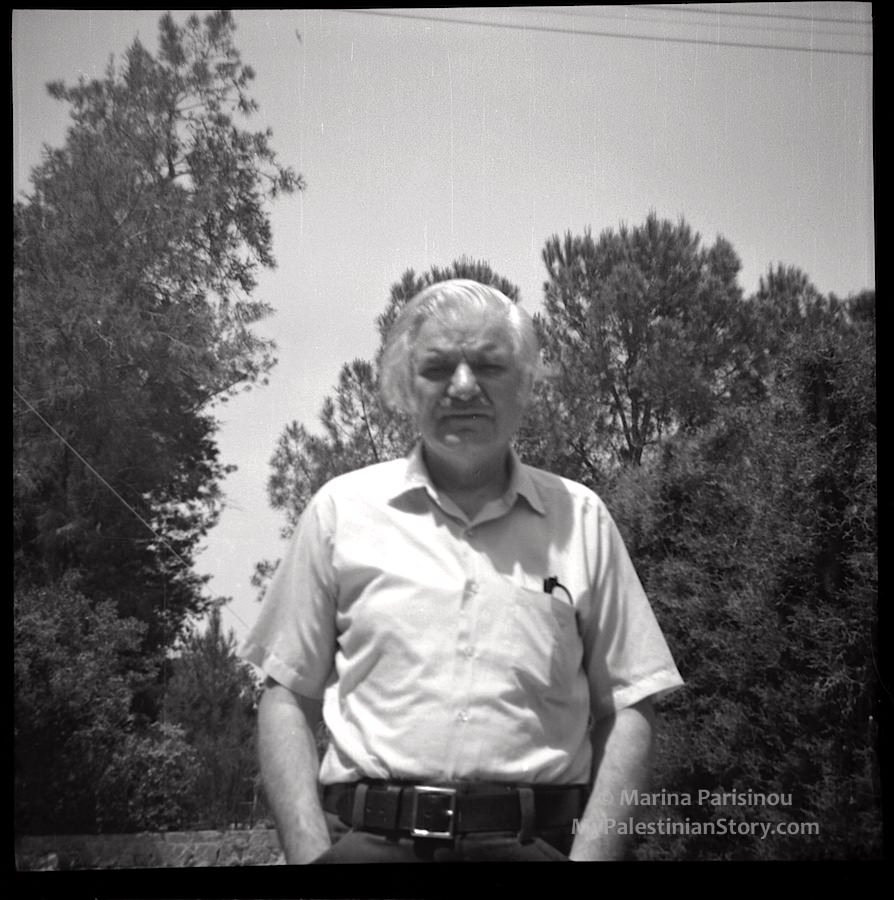

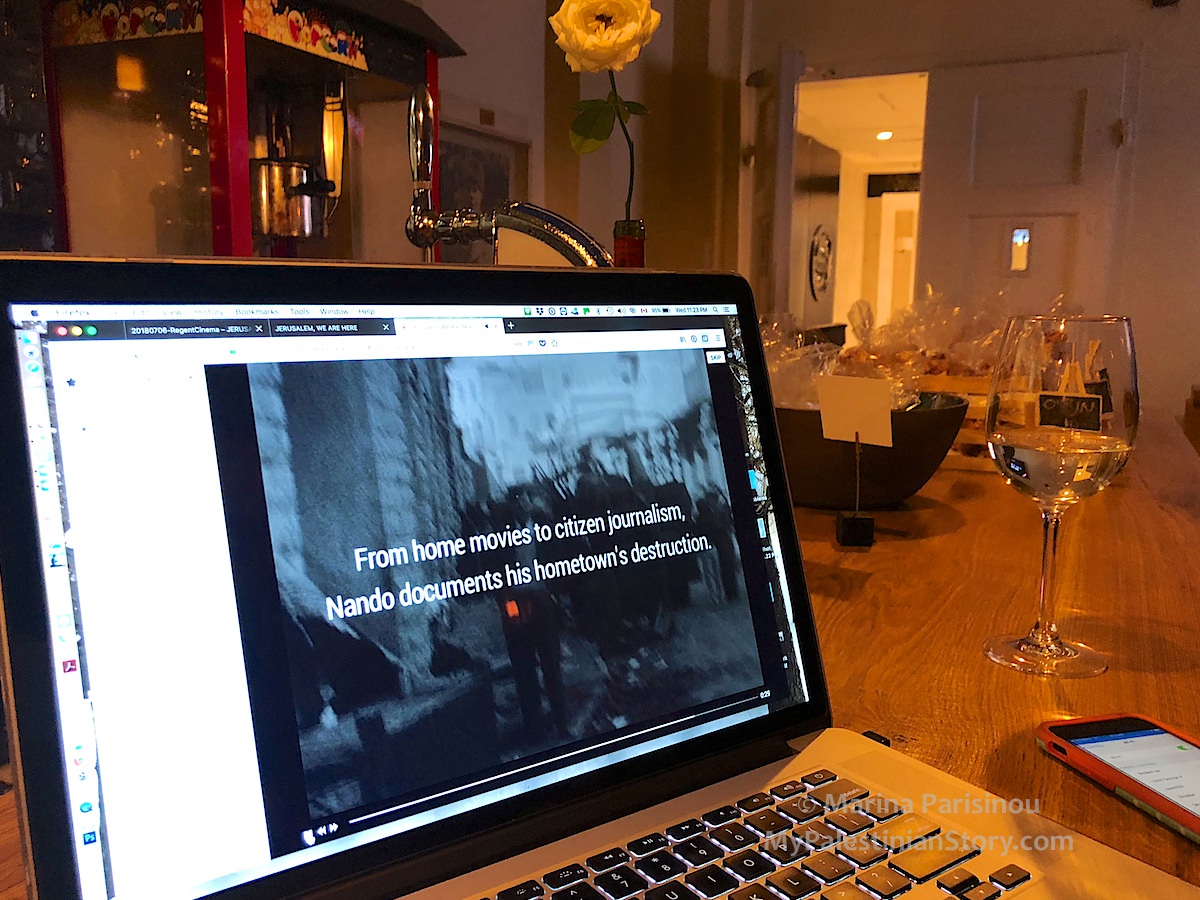

The old reel begins with shots of just that – REGENT CINEMA emblazoned across the top of the building. “New Programme Every Monday and Thursday.” And then a head shot of the Regent’s 1940s owner, Ferdinand (Nando) Schtakleff.

I’m sitting quietly somewhere in the back with a friend. I have no role in this particular part of the documentary but I wouldn’t have missed this afternoon for the world. Nando was my great-uncle, my maternal grandmother’s brother. I’m in his cinema and he’s up on the screen. I can’t stop the tears rolling down my cheeks.

This clip, one of a series showing their life in Jerusalem in the mid-1940s, was given to our family by Nando himself, during one of his Cyprus visits, on a VHS video tape. In turn I had it transferred to DVD and from there I extracted the individual clips so I could share them with the family online. I also shared them with the project when I first joined and then asked Cynthia, Nando’s daughter, for the originals as we had hoped to have them digitally restored. Sadly she couldn’t find them but she did locate, among her father’s films stashed in their New York basement, a couple of others from their Palestine days . One of them, which we named Seaview, can be seen in full in JWRH (and is dedicated to Cynthia’s memory). As a result of these clips, which are the only archival film the project has, the Regent became the starting point of JWRH and Nando one of its stars.

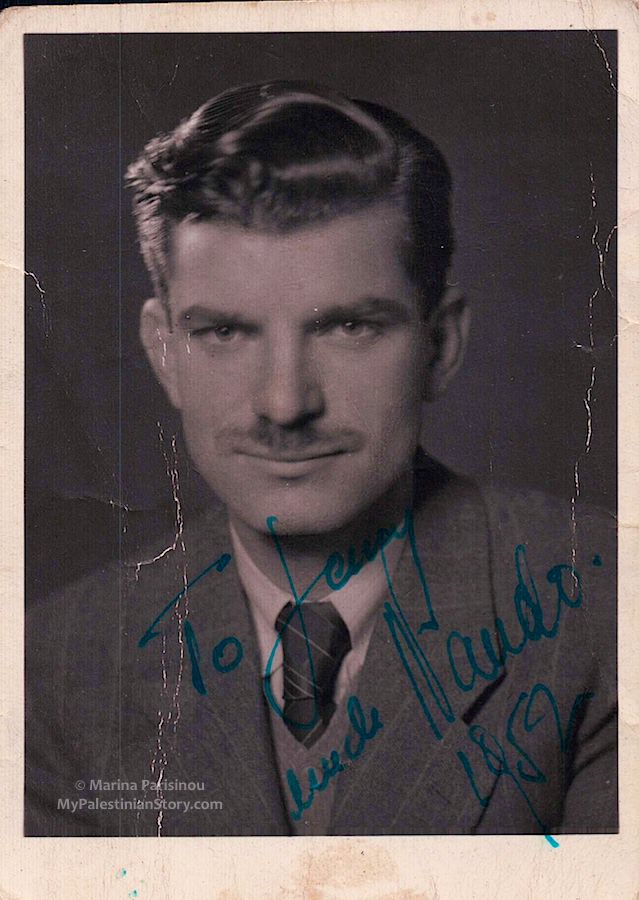

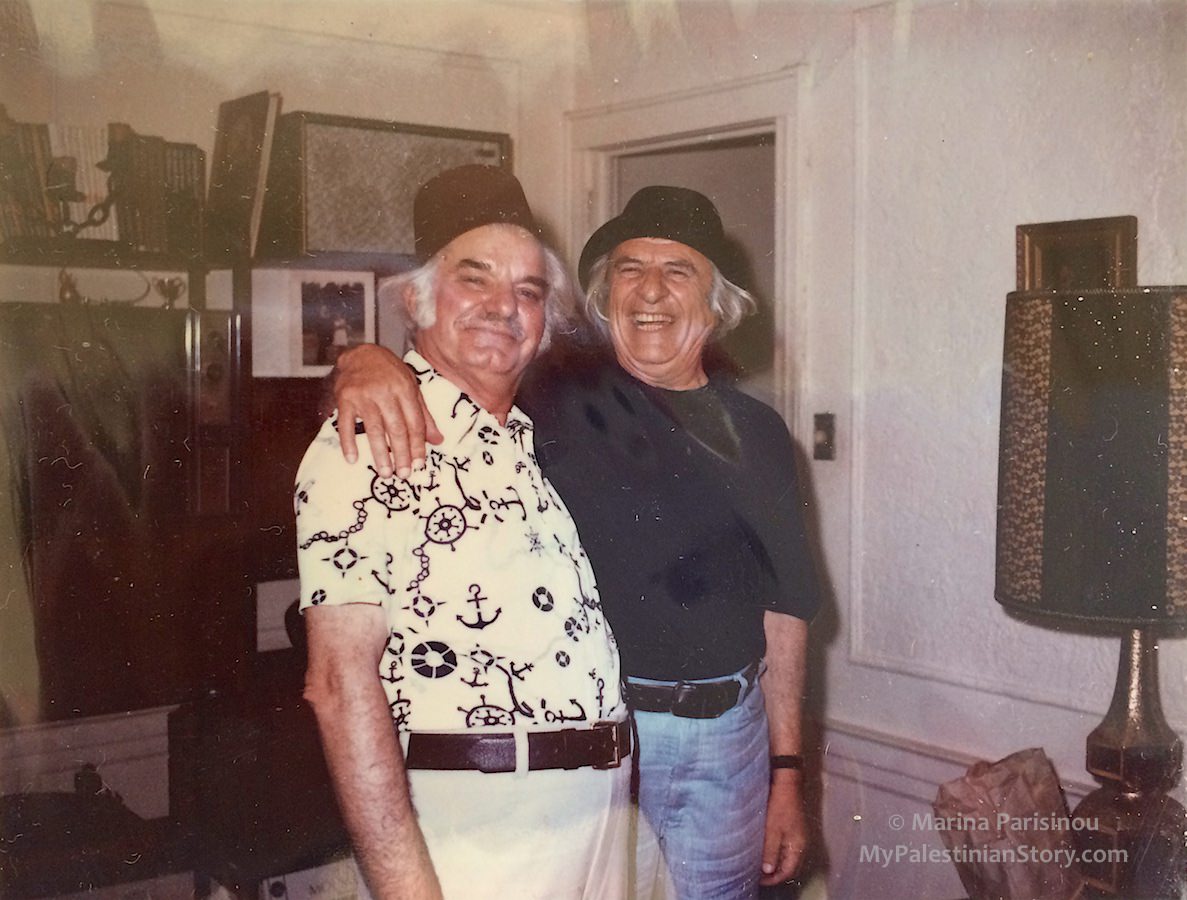

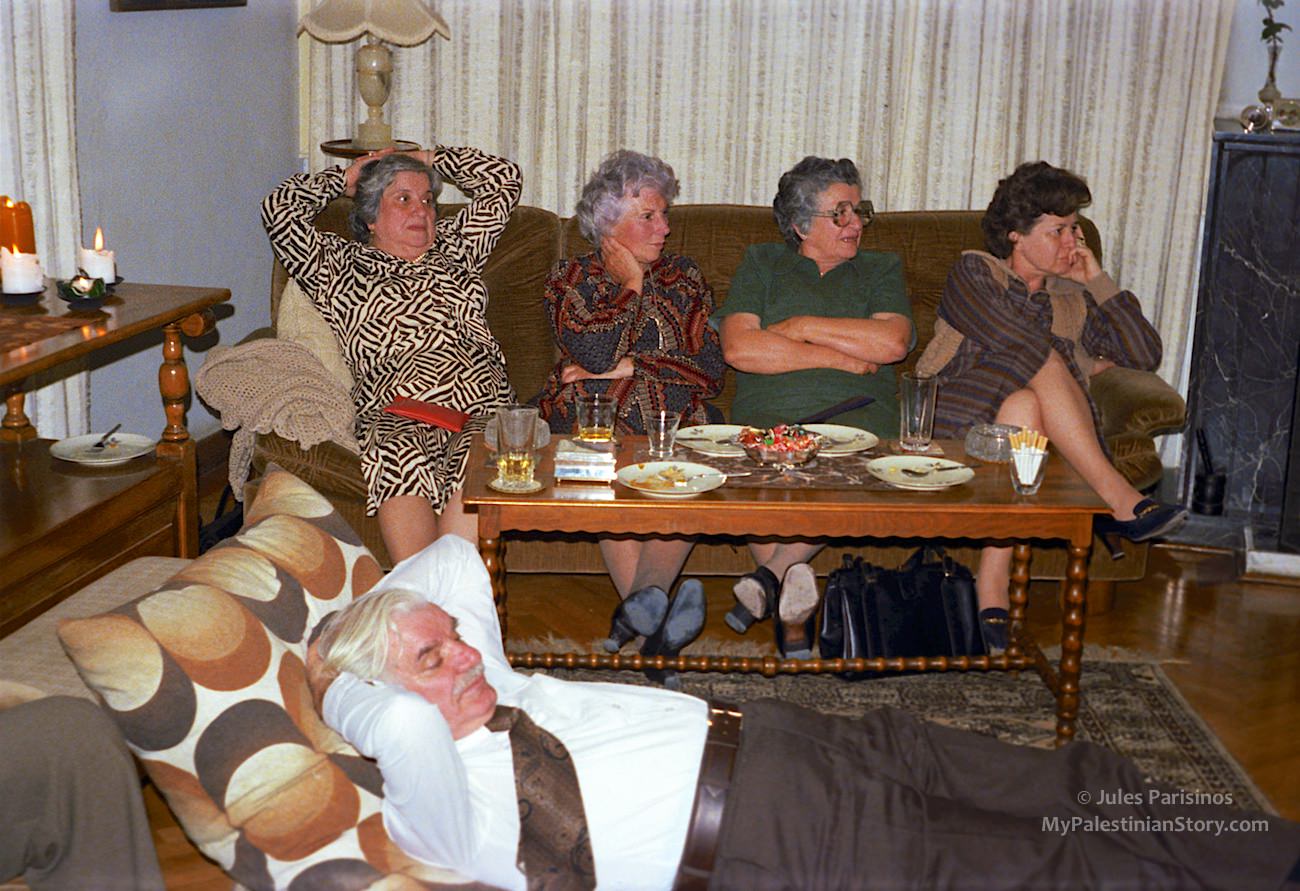

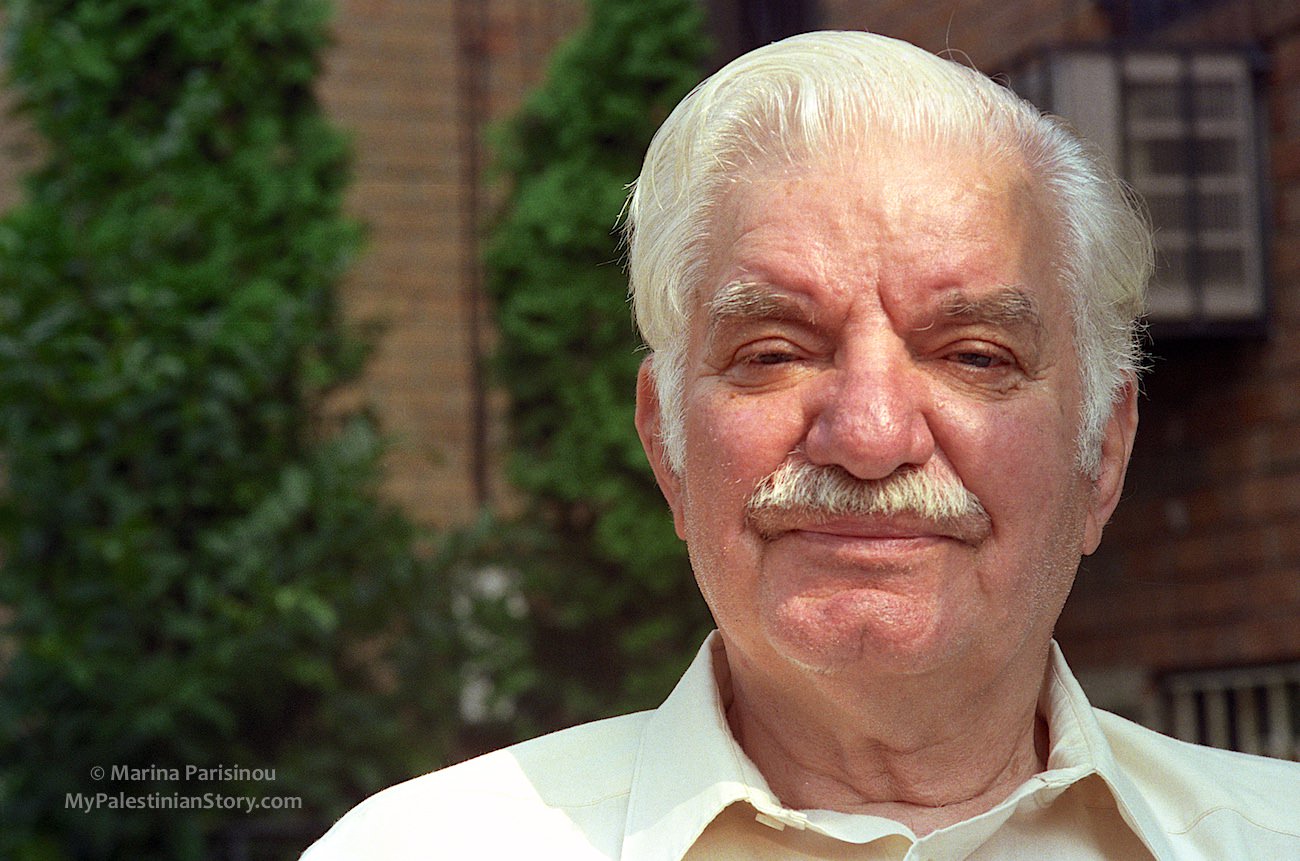

He was always a star in my book – and not mine alone. With his Clark Gable looks and larger-than-life presence, his visits to Cyprus were occasions to remember for all the family: always with a camera in hand or behind a projector, commanding everyone’s attention, as he projected these old Jerusalem films or his travel adventures on our living room walls, having first selected some suitable instrumental background music from my parent’s LP collection; or telling jokes and stories with big guffaws; or drawing for us kids and making faces, his white mustache jumping up and down. Attempts of taking candid photos of him were swiftly thwarted with a rebuke and a bulging of his light-blue eyes! Ample notice had to be given so the comb he kept in his back pocket could first be deployed across his full (white, by the time I knew him) mane complete with sideburns.

In our family’s parlance, Nando was synonymous with films. I don’t know how this passion of his came about but it started at a young age.

He was born on 19 January 1915 in Jerusalem, the fourth surviving child (my grandmother was the first) of a father with roots in the Balkans and a Greek mother from Asia Minor. John, his father, was in the flour-mill and bread-baking business and his mother, Eugenie, had been a dramatic actress until her marriage. The end of Ottoman rule in Palestine resulted in a downturn in John’s finances who had supplied the Ottoman army with flour and bread. The British were not inclined to do business with him so John went to Istanbul hoping to collect on his debts from his old customers and in 1922 he moved the family there for a couple of years (except for my grandmother who had just got married). After a short time back in Jerusalem they returned to Istanbul for a couple of years more. By the time they were back in Jerusalem for good, Nando must have been barely a teenager.

On the left, seated: my grandmother Paraskevi (Vitsa); standing: Constantine (Coca); seated in front of him: Ferdinand (Nando). On the right, standing: Marika; seated: Nicolas (Colia) – late 1910s

Was his love of film and movies a case of love at first sight? Did it come about when he saw his first movie? Was it a silent one or a “talkie”? Where did he pick up the bug? In Jerusalem or perhaps during their Istanbul stints? So many questions I wish I’d thought to ask him.

At the time of his birth, cinema was still in its infancy having kicked into life in the late 1870s with stop-motion pictures, followed by the kinetoscope some years later. In 1985 the Lumière brothers were the first to project a motion picture before a live audience, and hand-painted frames introduced the concept of colour in movies. In 1914, Hollywood had its first hit: The Squaw Man. The industry continued to evolve rapidly with innovation following innovation. In 1927 The Jazz Singer was the first film with synchronised dialogue while colour was not used extensively until the introduction of the three-colour process in 1932.

By that time, Jerusalem already had a vibrant cinema scene.

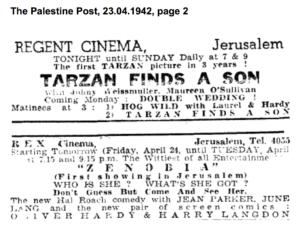

At first, movies were shown in impromptu settings or makeshift venues. Rachel Neiman writes: “Even before 1900, Samuel Feig, a Jerusalem Templer, was screening silent films at a Jaffa Gate coffeehouse. In 1908, the ‘Cinematographe Oracle’ offered ‘living pictures’ twice on Saturday and Sunday nights, and once on Thursdays. In 1912, a silent movie theater, the ‘Cinema International’, opened in Jerusalem on the second floor of Feingold House on Jaffa Road. However, the screenings, consisting mainly of silent feature films and documentaries, were not held at fixed times but instead began based on the number of tickets sold. Shows continued until after midnight…“

The first proper cinema in Jerusalem, as far as I can determine from my research (primarily on the internet – not to be misconstrued for academic!) was Zion Hall. In its first incarnation in 1912 (or 1916 according to some sources) it was no more than a shed on the corner of Jaffa Road and Ben Yehuda street, on a plot that previously belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church. Power was provided by a generator and the screen was a white sheet. When the roof caved in following a heavy snowstrom in 1920, it was replaced by a 600-seat grand theatre that became the main venue for perfromances in Jerusalem.

A few blocks away, where Agripa’s Way met King George V, Eden Hall, “… was designed by architect Nathan Brinn in the International Style and was covered with rough, gray plaster rather than the usual Jerusalem stone. Audiences enjoyed a spacious hall, where they saw the latest productions from Hollywood, and where, throughout the years, political lectures and meetings took place too.” (Haaretz, 19 Oct 2011)

Two blocks behind the Zion was the Orion. “The movie theater was established in 1938, as a Jewish-Arab business of Daoud Dajani, the Dabah family and Ezra Mizrahi. The unusual façade of the Orion was designed by the architects Dan and Raphael Ben Dor, in the style of Radio City Music Hall in New York. The impressive glass exterior is still there. In 1943, the business partnership dissolved and the Mizrahi family became the sole owners.” (Haaretz, 23 Oct 2018)

Some 500m to the north, the Edison, the most luxurious of them all in its Art Deco style, designed by architect Ritten, while the foyer and the inner hall were the work of Orion’s architects, Dan and Raphael Ben Dor, opened in 1932. It served as a cinema, a theatre, a concert hall, an opera house and a cultural centre. Its stage was graced by names like Klemperer, Toscanini, Juliette Greco, and, legend has it, Umm Kalthum.

Then there was the Rex on Princess Mary Avenue, which opened in June 1938 to much fanfare, “crowds and a holiday atmosphere” which included a stage appearance by a balalaika troupe. “The inside of the hall, which seats 1400, is attractively decorated in a colour scheme of fawn and red and in modern style.” (The Palestine Post, 17 Jun 1938)

Less than a year later, on 29 May 1939, five people died and eighteen people were injured at the Rex when the Jewish terrorist organisation Irgun detonated mines inside the cinema during a crowded evening performance. The Military commander of Jerusalem District issued an order at midnight: “Whereas certain persons have placed bombs in the Arab-owned Cinema, Rex, on the evening of May 29, 1939, thereby causing grievous hurt to many persons, I hereby order that the Eden, Edison, Orion and Zion Hall Cinemas within the Municipal Boundary of Jerusalem shall remain closed until further order.” (The Palestine Post, 30 May 1939) The Rex reopened in less than a month by which time all six of the city’s cinemas were back in business.

The last cinema of the British Mandate era was the Tel-Or, situated between the Zion and the Eden. It opened in July 1941, premiering with The Gypsy Baron, “a film based on the famous operetta by Johan Strauss” according to The Palestine Post.

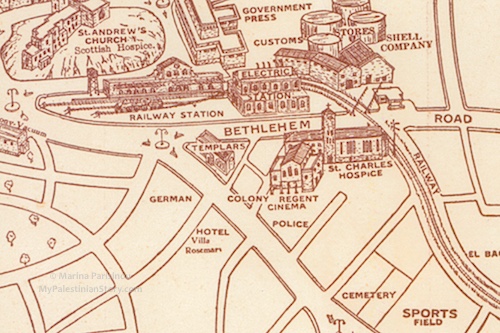

All these cinemas were located within blocks of each other, in the commercial centre, north-west of the old city walls.

And then, a couple of kilometers to the south, in the quiet, mainly residential German Colony founded in 1873 by German Templers (an evangelical sect that had seceded from the Lutheran Church in 1854, not to be confused with the Crusader Templars) the son of Templer architect Gottlieb Bäuerle set up a cinema next to the house his father had built for the family on Lloyd George street. It was an unusual building for Jerusalem and for the German Colony itself, more in the Tel Aviv style, constructed of silica blocks, with a big theatre on the ground floor and a residential floor above it. Initially the Bäuerle Cinema Hall was used mainly by British troops. In September 1934 it served as a polling station where municipal candidates for Division III, Nakhleh Eff. Kattan and Anastas Eff. Hanania, faced off.

From 1931 to 1937 the second floor above the theatre was rented to various families. Khalil Sakakini lived there before moving into his Katamon house.

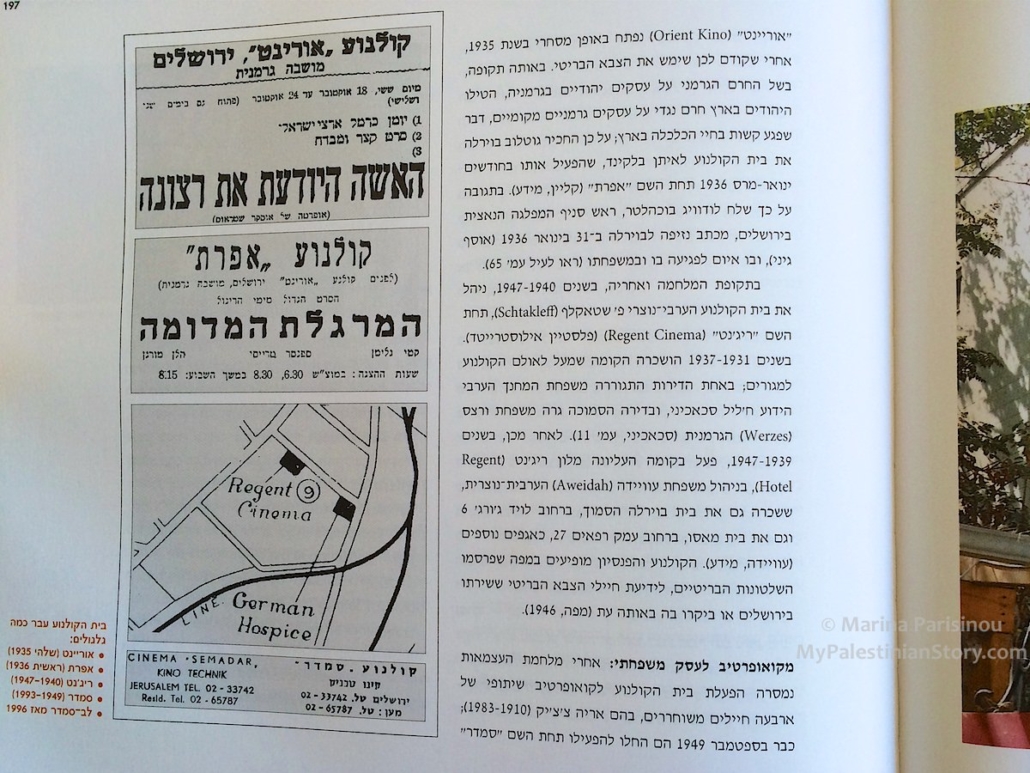

In 1935 the theatre was launched as a commercial cinema, open to the general public, under the name Orient. On opening night, Friday, 8 February, its 400 seats were fully occupied. “The film ‘Three on Honeymoon Trip,’ featuring Brigitte Helm, and advertised as an Austrian production, was well received by the audience, among whom were a number of well-known German Colony residents. The management says that English-speaking films including English newsreels, will be shown shortly at the Orient.” (The Palestine Post, 10 Feb 1935)

A year after its opening, an item in The Sentinel (20 Feb 1936) announced: “Nathan L Goldstein, New York attorney and a director of the Industrial and Finance Corporation of Palestine, Ltd, is head of the newly-established Palestine Cinema Circuit, Ltd, which intends to run or lease first-class picture houses in Palestine. American films are to be preferred. The Cinema Circuit has just taken a three-year lease on the Edison Theater, Jerusalem, and has also assumed charge of the German-Christian owned ‘Orient Cinema,’ which has been renamed ‘Eprath’.”

This was a result of the boycott that German businesses in Jerusalem were subjected to in response to the rise of the Nazis in Germany. With the outbreak of World War II, Germans in Palestine were classed as enemy aliens and “four Templer settlements were sealed off and turned into internment camps.” (BBC.com) Their houses came under the control of a newly created department, the Custodian of Enemy Property. By the mid-1940s there was hardly anyone left of the German community in Jerusalem.

The new name for the cinema was actually Ephrat. I’m not exactly sure what “assumed charge” was intended to convey but this name appeared in newspaper columns for cinemas for only a few months, until May 1936. By December of that year, mentions of the Orient Cinema appeared again in the press.

However, as far as contemporary Israeli press is concerned, the cinema was turned over to Jewish management and that was that, until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. There is a standard blurb that appears, at least in the English-language press to which I have access, which seems to get copied from one paper to the other, with only minor parphrasing, and has even made its way into The Guardian. It’s hard to tell where it originated but what it does is gloss over the period from the late 1930s until 1948, thus erasing more than a decade of the cinema’s history. An example: “… a boycott was declared against German-owned businesses, in response to the Nazi ban on Jewish businesses in Germany. To prevent its closure, the Orient’s German owner turned it over to Jewish management, a stunt frowned on by the head of the Nazi Party branch in Jerusalem. After 1948, the theater came into the hands of four demobilized soldiers, including Arye Chechik.” (Haaretz, 9 Apr 2008)

When I first came across these fascimile reports, my suspicion was that they must have come fromDavid Kroyanker, the Israeli architect and self-appointed guardian of Jerusalem’s architectural history who is the go-to interviewee ubiquitous in the Israeli media. His books are in Hebrew but an on-the-fly translation by Dorit proved me wrong: Kroyanker himself does acknowledge the rest of the history.

The frown of the local Nazi party, referred to in the Haaretz article above, must have been what gave rise to another deal mentioned in The Palestine Post (4 Sept 1939) dated 9 August 1937, between Herr Bäuerle and Talhami Brothers Co who “undertook to pay the rent and agreed … to keep, perserve and maintain the cinema and inventory in good repair and order, and to use it exclusively for holding therein cinema, theatrical or musical performances…” Indeed, the Talhami Brothers representing the Orient participated in a meeting with other cinema owners on 9 September 1937 during which a Mandate official impressed upon them the Government’s requirement that they are punctual, starting their programmes on the advertised times and ending them no later than 11:45pm! It remained under the Orient name till the end of 1939. In November 1939 The Palestine Post wrote: “In honour of Ramadhan, the Rex and Orient Cinemas are each presenting Arabic pictures this week.” (Incidentally a Michel Talhami is mentioned in 1946 as one of the partners in the Rex which may explain the coordinated action.)

Kroyanker doesn’t mention this but does say that from 1940 Ferdinand Schtakleff managed the cinema. He refers to him as an Arab Christian, conflating perhaps the Talhami deal with the subsequent one, that of Nando’s.

with the Regent in the centre. (Click to enlarge)

How exactly it came about I don’t know. What is clear is that Nando never lost his passion for movies, not even after his father burnt all his films presumably in order to knock some sense into him and push him to get a “real” job. And although he had a real job of sorts – an electrical shop on Emek Refaim street, just round the corner from the cinema, in which his older brother, Coca (Constantine), repaired all manner of electrical appliances, Nando at the age of 25 became a cinema owner in war-time Jerusalem. He took over the Orient, rebranded it as the Regent and ran it until they fled the city in 1948.

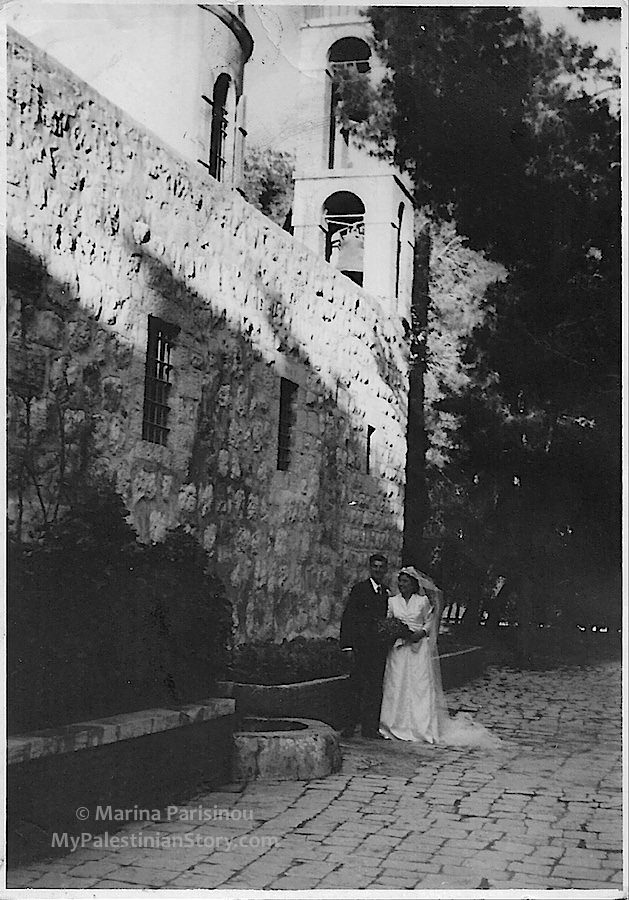

Around that time he married his beloved Effie Sfaelou, a Greek Jerusalemite, and by December 1942 their daughter Cynthia had come along, followed by a son, Alex, three years later, in November 1945.

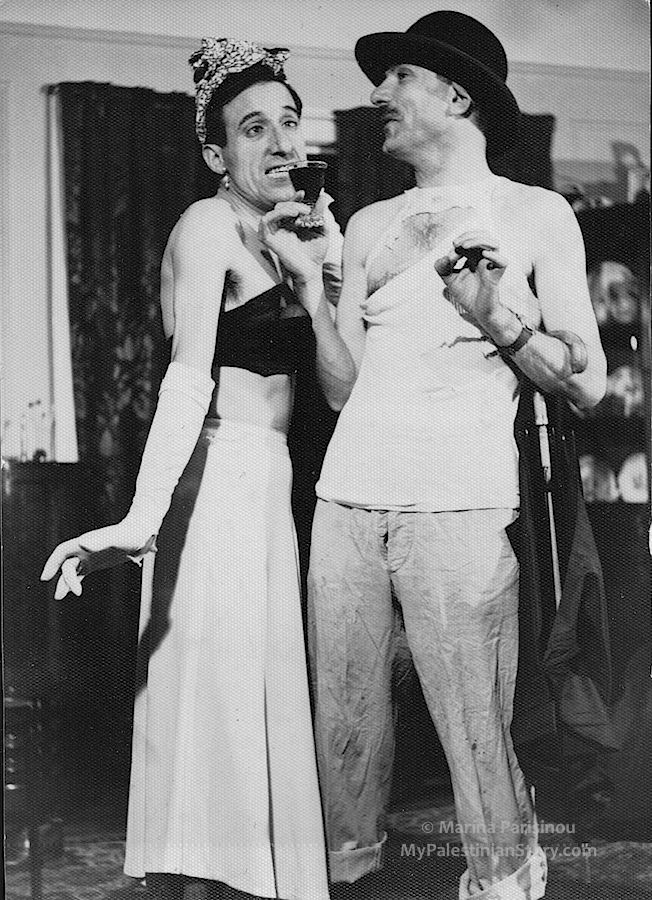

In his cinema venture, he had a partner: Bill Thorogood who was married to Marika Gaitanopoulou, a Bezalel-trained painter and sister of Efthymios Gaitanopoulos who married Nando’s sister, also called Marika. So I suppose you could say Nando and Bill were in-laws… once removed (no, you won’t find this term in genealogy books!)

Nando must have somehow got wind of the fact that the Orient was looking for a new owner as Germans were leaving or being deported (I don’t know which was Bäuerle’s fate). After all, Jerusalem was a small society at the time, his shop was round the corner from the cinema (having said that, it’s an assumption on my part that the electrical shop preceded the cinema) and Nando lived close by. The temptation must have been too much to pass up. But he was short on money so he approached his “in-law” Bill Thorogood and (as John Thorogood, Bill’s son, has confirmed) asked him to finance this enterprise.

William A Thorogood was Chief Clerk of the Central CID (Criminal Investigation Department in Brit speak). According to a short bio from The Palestine Post (10 Mar 1940) he “joined the military administration here in March 1920 and was in the Civil Administration from July 1920. He first served in the Secretariat and was transferred to the CID in 1932.” The Post offered a consolation: “His friends will be glad to hear that he is not leaving the country after retirement, but intends to remain in the public eye as the lessee of the Regent Cinema (formerly the Orient) in the German Colony, Jerusalem.“

It sounds like the timing was just right for Thorogood’s involvement – a retirement project, as it were. He would be a silent partner and Nando the Managing partner. After all, it was Nando who was dragged to court to account for a mishap. With the outbreak of World War II, the British authorities had imposed a blackout in Palestine to prevent enemy bombings. In June 1940 The Palestine Post was reporting that “On the whole the blackout in Jerusalem has been pronounced satisfactory” with “only defects due to carelessness.” One such “defect” occurred at the Regent. “… on July 20 the cinema was leased to the RAMC [Royal Army Medical Corps] for a dance, and a number of senior officers attended. At 10.30 a police-constable and an ARP warden saw lights streaming from the three double-doors of the premises. Half an hour after they had complained to the proprietor, two of the doors had been closed but the third remained open and the lights continued to be visible up to about midnight.” The Jerusalem Chief Magistrate passed “a nominal sentence on the owner of the Regent, Mr Ferdinand Schtakleff…” who “pleaded that he had relied on the undertaking of the Secretary of the Dance Committee that he need not worry about the blackout.” The article concludes with the following editorial comment – with which I can’t help but wholeheartedly concur! “Yet the obviously flagrant non-compliance with these requirements on this particular night did not appear to have been a matter of great concern to the members of HM Forces present at the time to whom, in the nature of things it must have been apparent.“

Although it hosted all sorts of events, the mainstay of its business was commercial, American for the most part, movies – with no advertising interrupting the two-hour show, as Nando was quick to point out in April 1941 in response to a Letter to the Editor of The Palestine Post by someone complaining about the number of commercials shown in Jerusalem’s cinemas.

From 1939 to 1947, the second floor of the building was the Regent Hotel, operated by the Aweidah family who also rented the Bäuerle house next door. (For more on the Aweidahs, see the Green Tour of JWRH)

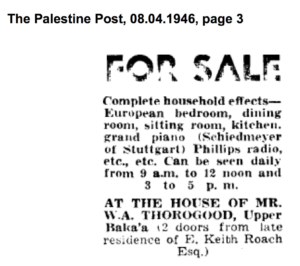

With the conclusion of WWII, the “troubles” between Jews and Arabs picked up steam and before long, life for Jerusalemites began to unravel. Bill, probably having read the writing on the wall, decided to return to England. Early in April 1946, the Thorogoods put their household effects on sale, and Bill sold his share of the Regent to Nando.

In July 1946 the wing of the King David Hotel that housed the British Secretariat was bombed by the Irgun, causing major destruction and the death of over 90 people. (Presumably Bill was already back in London when he heard the news. I wonder what his thoughts were, given that earlier in his career he had worked for the Secretariat.)

The British set up security zones in Jerusalem and issued special passes to control movement. In another clip of Nando’s we see him at the checkpoint at the Abdeen roundabout (by the Louisidis property).

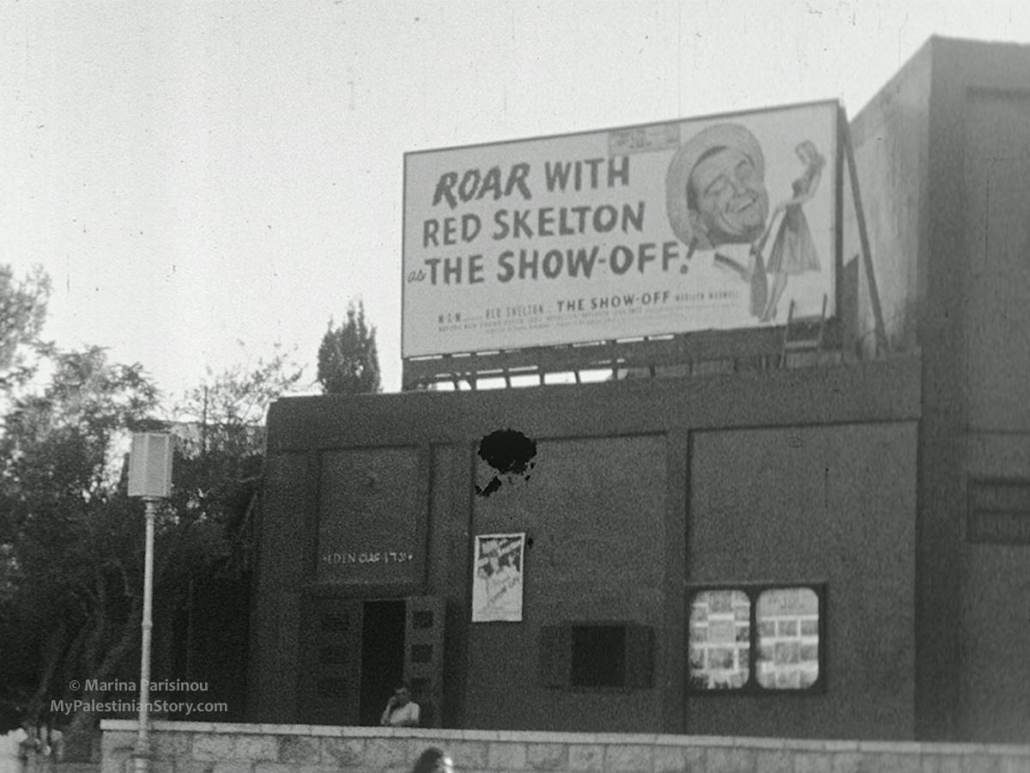

In the riots that broke out in Jerusalem following the 29 November 1947 United Nations’ vote to partition Palestine, the Rex went up in flames once again when the Irgun broke into the projection room, threw spools of film on the floor and set them on fire. A big, black column of smoke marred Jerusalem’s skyline and the building was reduced to a shell. In the days that followed, Nando wandered over there with his camera and documented the destruction (see Seaview in JWRH).

And then the bombing of the Semiramis Hotel in Katamon on 5 January 1948 precipitated a mass exodus of residents of south-west Jerusalem. The Regent disappears from newspaper listings from early January, with only the Eden, Edison, Orion and Zion remaining. Tel-Or reappears at the end of the month.

The Regent shows up again in February as the venue for the drawing of Bearer Bond issues (not quite sure what that was about) while a week or so later “information was received that the Regent Cinema … was to be blown up … the building was evacuated and searched, but nothing was found.” (The Palestine Post, 15 Feb 1948)

I don’t know if Nando was still there or had already fled with his family in search of safety. At some point, before the end of the British Mandate, they joined the exodus to Egypt where they, along with hundreds of other Palestinians, were refused entry at the border and detained at Kantara, an old British army camp. They decided to return to Jerusalem, only this time they stayed in the old city, which was by now under Jordanian rule, as their old neighbourhood had been taken over by Zionist forces which prevented their return.

The influx of refugees from what came to be known as West Jerusalem – the neighbourhoods of German Colony, Greek Colony, Katamon, Baq’a, Talbieh – and beyond, put a strain on resources such as water and electricity and even food. John Tleel writes about the Imperial Hotel, just inside Jaffa Gate: “During those abnormal days a small cinema started functioning within the hotel, entertaining those thirsty for amusement. Nando Chtakleff [sic] of the pre-1948 Regent Cinema in the German Colony was the initiator. Most of the audience was young people, children and teenagers, and we were among them. The old films and the frequent interruptions caused by the malfunctioning generator were comedy in themselves.“

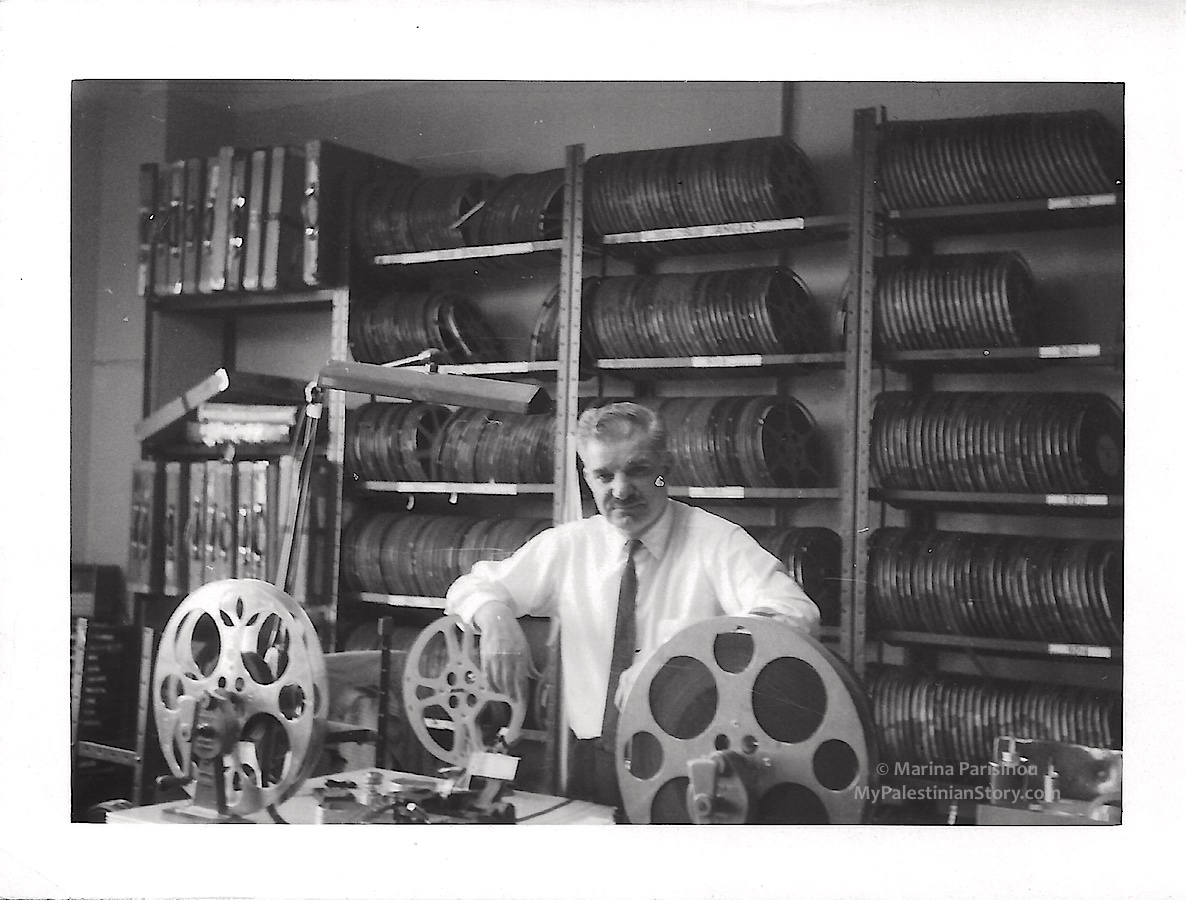

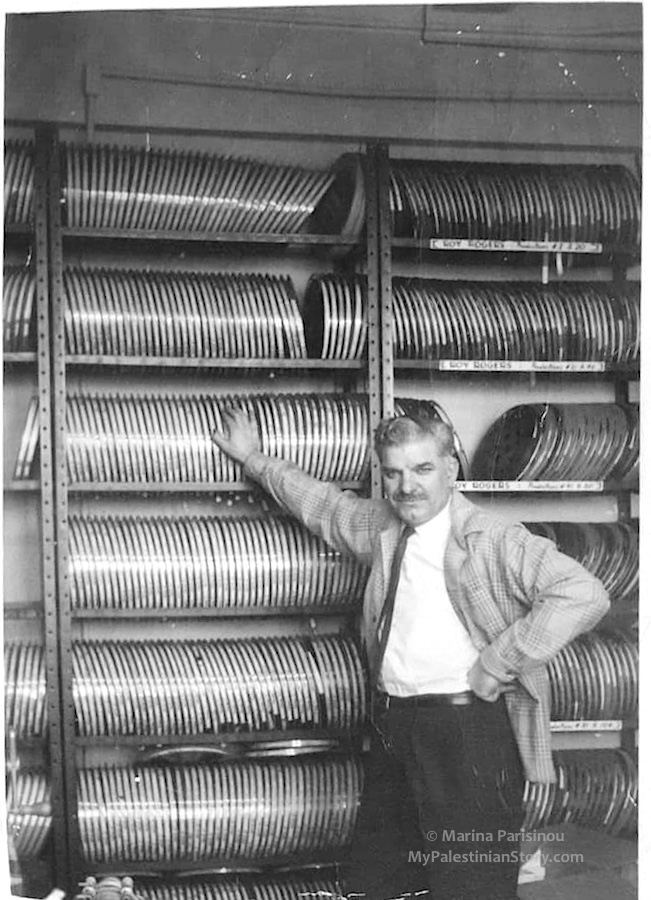

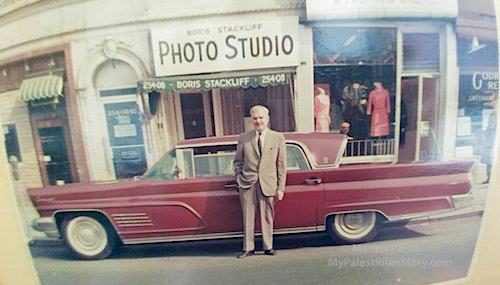

Nando and his family eventually settled in Sheikh Jarrah for a couple of years. In mid-January 1952 they were on a ship sailing from Naples to New York City which they adopted as their new home. Nando was employed in various film studios where he would continue to be involved with his favourite medium. Their Jerusalem life was over for good.

~ Slideshow: Nando & family ~

But for the best part of a decade his Regent had been a nucleus of entertainment for many of his fellow Jerusalemites and continues to live on in family lores and still-vivid memories.

Anwar’s grandfather Fou’ad had his first date with his grandmother there. Mona’s maternal grandfather was a member of the Censorship Board which held its screenings at the Regent, reviewing films to ensure that they did not exceed the standards of decency of the times (or perhaps promote subversion?) Mona’s mother would beg her father to take her along to the screenings and he would often give in.

Ellie Savvidou (née Louisidis – see the Green Tour on JWRH) recalls how her older brother George didn’t want her to tag along when he went on his dates with… my mother (she was his first girlfriend) to the Jewish cinemas so he’d promise her instead yummy confectionery from Kupulsky’s, next to Zion Hall. But my mother did not approve of his bribing tactics so George would compromise, offering his sister a visit to their neighbourhood cinema, the Regent. Ellie’s close friend, Anna S, remembers the Regent as their regular Sunday outing, where they’d catch the matinee at 3pm. On one occasion, her piano teacher, Stratis Gaitanopoulos, prescribed a harsh punishment for her failure to play a piece right: he banned her from going to the Regent the following day. Ouch!

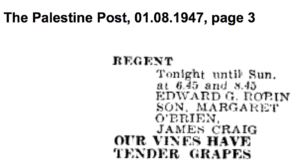

Salwa G was only about 10 but still remembers seeing child star Margaret O’Brien at the Regent in 1947. It may well have been in Our Vines Have Tender Grapes.

Issa Mahshi and his brothers had free passes to the Regent. Nando was the family’s tenant in a house on Emek Refaim street. So Issa didn’t miss a movie. Every time the movie changed, he was there. He remembers Nando changing the posters in the glass display outside. He also explained that the wooden benches I had heard about were not the only seats in the house, just the cheap ones! Pricier tickets came with commensurately plusher seats. He also remembers Friedrich, the German employee who was at the door and his daughter who also worked at the Regent, as well as a guy called Issa. The Germans were presumably bequeathed to the Regent by the Orient.

The daughter must have been the woman my mother remembered as a stereotypical German who was – stereotypically – in charge of law and order at the cinema which she imposed on rowdy youngsters with the aid of a… stick!

Nando’s relatives revelled of course in having the cinema in the family. My mother and my aunts always got very animated when talking about the Regent. Mum’s cousin Feely Antipas (née Gaitanopoulou) remembers how Saturday afternoons at the Regent were her favourite time when her beloved uncle Nando would invite her and all her friends to movies like Flash Gordon, Tarzan, or westerns. She took pride in being able to stride into the cinema for free, accompanied by a gaggle of little friends, and taking over the best seats.

Today the Regent is the only one that survives from the British Mandate era. It is in fact the longest-running cinema in Jerusalem.

The Zion was demolished in 1979, having been shut for the previous seven years, and a bank was built in its place. The Orion closed down about a quarter century ago and became the first MacDonald’s in Jerusalem. Recently it has been converted into a hostel called Cinema Hostel with 170 beds and design nods to its original form. The Edison ceased to operate in 1995 and was demolished in 2005 having fallen victim to a battle of religion vs secularism. Around 2011 the Eden was demolished completely to make room for a 24-story luxury residential and business project. Not sure what happened to the Tel-Or or if the Rex ever came back to life after it burnt down in 1947.

But the Regent is still standing and operating as a commercial movie theatre, now under the name Lev Smadar. In 2008 the 80-year anniversary of the cinema was celebrated over two days, thanks to David Kroyanker who had just published his book “The German Colony and Emek Refaim Street“.

It hasn’t all been smooth sailing though. On a couple of occasions its imminent demise was prevented by its fans and supporters in the community who put up a fight for its survival.

In May 2011 the cinema, which has been part of the Lev Cinema chain since 1993 and has become a cinema-lovers’ place – in contrast with more commercial venues – came under threat by real-estate developers but the local community and film lovers rallied around it and managed to save it.

In 2016 its future was all up in the air again, when some major retrofitting was required which the landlord was unwilling to pay for. Once again the community stepped up to support the efforts of the Lev chain and the municipality’s to keep it open. They staged a crowdfunding campaign urging people to buy “honorary” subscriptions. The plan worked. The cinema closed down only temporarily for major repairs. On the @donotcloselevsmadar Facebook page, one person wrote: “We were at the temporary farewell party tonight. We shed tears in the movie … and we also made a subscription of respect for the Smadar cinema!” In July 2017 Lev Smadar re-opened to the joy and relief of many, looking spiffier than ever with comfortable red seats, a nice bar and restaurant, and all the bells and whistles of technology (system for the hearing impaired, 3D technology, surround sound system etc.

And so we were able to film there. The management is quite progressive and were open to our project which made us feel good – and would have pleased Nando.

Before filiming, we had visited the place and taken photographs, two years in a row. I was particularly keen to identify the tower on which “Regent” had been written in Nando’s time, as seen in his clip (see below). There’s a tower visible from the street but that seemed part of the hotel on the floor above. The geometry didn’t quite fit but I assumed that must have been it, attributing the inconsistency to all the changes the hotel had undergone through the years. The courtyard, in which Nando in the clip is shown arriving in his car, had now been enclosed and was a cafeteria.

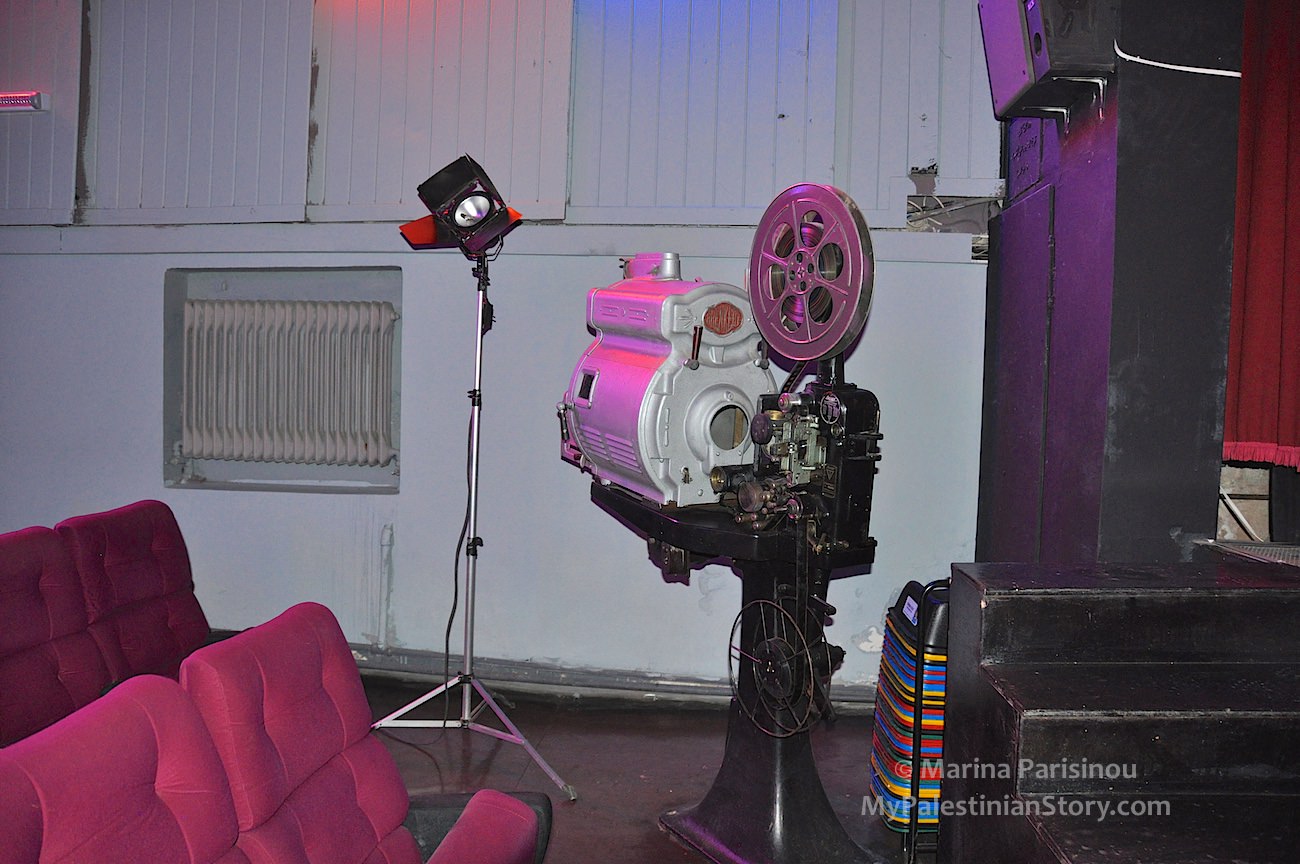

Dorit thought that the old machine they displayed at the entrance (no longer there) must have dated to before his time, probably used to spool back the films.

Another machine, slightly newer, was displayed inside the auditorium, which Dorit thought may also have been from Nando’s time.

As we projected Nando’s clips on the screen, the projectionist of Lev Smadar, a bulky man, bald, with a slight stoop and no trace of smile on his face, stood at the back and appeared to be transfixed by the old images of the building he knew intimately.

When the filming was over, Dorit interrupted my tears: Come, see! The projectionist had identified the tower: it’s where his cubicle was located. Through a back door we were led to an open space not accessible from the street. Look up! There it was, on a tower, barely discernible under the new paint but still there, traces of: New Programme every Monday and Thursday. My spirits lifted! A small part of Nando was still alive in his cinema…

This past summer, July 2018, we went back to the Regent to screen Jerusalem, We Are Here. Doing so on the 70th anniversary of the Nakba made it all the more poignant. Dorit and I met there late the night before, for our tech check, and marvelled at the recent upgrades. The place really looked great.

The event was well attended, with about 120 people of whom Dorit recognised no more than a third. Much as we appreciate the support of family and friends, it’s gratifying to see our work drawing in people on its own merits. Ellie Louisidis-Savvidou had travelled from Cyprus especially, with her youngest daughter and two granddaughters, and was visibly moved as she made a short speech.

Our interactive documentary is keeping the memories of the Regent alive, along with those of other buildings and the people whose lives were aborted in this space.

The living owe it to those who no longer can speak

to tell their story for them.

— Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz

This story is for you, Uncle Nando. I owe it to you.

~ Slideshow: At the Regent ~

** This was first published in the author’s personal blog: MyPalestinianStory.com

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!