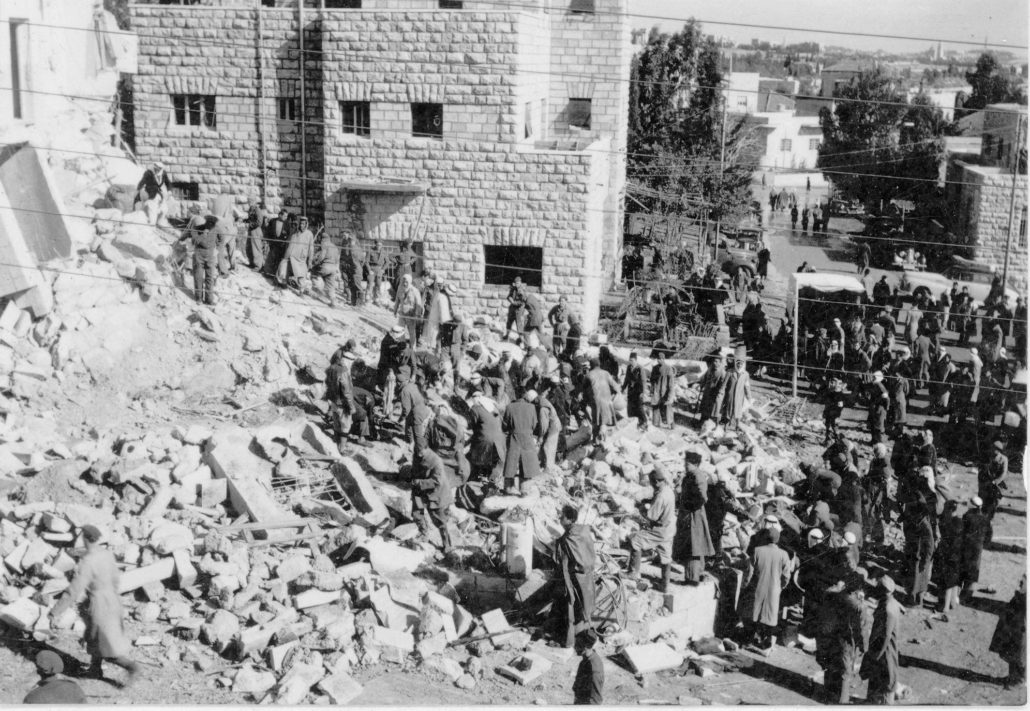

The August issue of This Week in Palestine (TWiP) is dedicated to West Jerusalem with the caption: ‘We Too Shall Never Forget.’ The term West Jerusalem refers to those neighbourhoods of Jerusalem, outside the walls, that were occupied by the new state of Israel in 1948 and as a result were cut off from the rest of the city (which was occupied by Jordan until 1967 and became known as East Jerusalem). German Colony, Katamon, Baq’a, Talbiyeh, Greek Colony were neighbourhoods of Palestinian middle classes of all stripes: Christian, Muslim, Arab, Greek, Armenian… ‘In May 1948, an entire educated, cultured, cosmopolitan, and vibrant community of Palestinians was decimated. True, many moved on and rebuilt what they had lost, but the scar remains and the injustice continues. Somehow, this scar is genetic and is passed on from one generation to another,’ writes Sani Meo, publisher of TWiP, in The Last Word of the issue.

Read more