Walking to “Unsettle”

Introduction

“Hearing Arabic in these streets and hearing about the people who lived here gives me double vision,” an Israeli woman told me emphatically. “I grew up in Katamon, and the Palestinian past of this neighborhood was never part of my landscape. I can promise you that I will never walk these streets in the same way!” she proclaimed. The woman was attending a guided walk, one of half-a-dozen public walks I guided or co-guided while doing research for, and production and dissemination of, Jerusalem, We Are Here, an online project designed with Palestinian and international audiences in mind. But as an Israeli engaged with uncovering a buried Palestinian past, I wanted to reach Israeli audiences as well. The engagement in the space had various manifestations, with public guided tours being an evolving core. The design of the tours was organic and intuitive, but my goal was to use them as an experiential and structured vehicle for considering not only the Palestinian past, but also the future, and Israeli responsibilities towards that future.

In a fraught political space with active and continuous forms of erasure and exile, walking, by itself, does not have the capacity to reveal entanglements or remake place. I first started learning the Palestinian history of the neighborhood from Ghada Karmi’s memoir “In Search of Fatima” and Khalil al Sakakini’s diaries. But as I physically walked Katamon, I had no anchors to any of the landmarks mentioned in the books. Even former public institutions do not have plaques identifying them, let alone individual houses. While most Israelis know they are walking in a former middle-class Palestinian neighborhood, the large Israeli flags, welded iron Star of David or Menorahs on gates and fences, and the street names, all work to suppress the Palestinian history. As a tour guide, if I wanted to activate not only an expanded understanding of the past, but also an implied present and imagined future, I would have to first unravel Israelis’ well-knitted narratives. In effect, I was working – gently – to “unsettle” Israelis.

As an immigrant to Canada, I am also working alongside Canadians who are responding to the collective amnesia with regard to atrocities against Indigenous people. I use the term “unsettle” following Paulette Regan’s call, in “Unsettling The Settler Within” (2010), for non-Indigenous Canadians to decolonize ourselves and to question our national myths. Regan argues that non-Indigenous people have to make room for Indigenous counter-history before solid and mutual Indigenous/non-Indigenous relations can be formed. Zionism was conceived as a national revival project, inspired by the Spring of the Peoples (1848) and by rising Anti-Semitism in Europe. But it was also imagined and structured in terms similar to colonial ventures in North America. Israel is not an imperialistic project as there is no imperium, or centre, elsewhere to be enriched by the colonial project. But it does share some ideologies with colonialism. Early Zionists called themselves pioneers (halutzim), or settlers (mityashvim), a language similar to the Protestant settlement project in North America. Similarly to the Manifest Destiny doctrine, the Jewish pioneers in Palestine (in the late 19th and early 20th century), believed they have a divine mandate to rule over the biblical ancestral land, and the newly formed Israeli consciousness perceived itself as superior to the Palestinian polity, as bringing forth progress and modernity, as improving the “native.” Before Israelis can start imagining a different political relationship with Palestinians, we have to uncover our collective amnesia about the settler-colonial aspect of Zionism, and become accountable for our part in it.

The walking tours I designed tried to make a space for an “unsettled” walk, one that uses knowledge to enable and encourage empathy, while at the same time harnessing empathy towards responsibility.

Counternarratives

On a beautiful Saturday morning in May 2017, some ninety people gathered in a municipal park near the St. Simeon monastery, which sits atop a high hill in southern Jerusalem. In 1948, the location was strategic: whoever controlled it would control south and west Jerusalem. A three-day battle raged between the PALMACH (elite paramilitary Jewish fighting forces) and irregular Arab forces, and eventually the Jewish forces, despite high casualties, won. Or at least, that is the myth recited to generation after generation of Israeli soldiers and high-school students touring the site. “The steadfast few against the coward many” is a common narrative trope characterizing important battles of 1948.

But like all mythical narratives, it is selective and politically motivated. In fact, when the Jewish soldiers managed to enter the walled monastery yard, they were surrounded by Palestinian fighters, led by the charismatic Ibrahim Abu Dayyeh. Both sides suffered heavy casualties and the PALMACH soldiers sent a radio message to the Jerusalem commander, David Shalti’el, informing him that they had only a handful of functioning soldiers, and therefore they must surrender. In his memoir, Shalti’el recounts how he wanted the soldiers to persevere, so he lied to them, telling them the headquarters had intercepted a radio communication in Arabic indicating the Palestinian soldiers were about to surrender. In the meantime, Abu Dayyeh went to ask the Arab Legion for more manpower and supplies. But the Arab Legion was under British officer Glub Pasha’s leadership, and Glub Pasha had no interest in southern Jerusalem, so they arrested the charismatic commander instead of helping him. Without a commander and with dozens of dead and wounded soldiers, the Palestinian fighters chained themselves to each other, and fought till death. As it happened, it was circumstance, not superiority (moral or militaristic), that led Israeli forces to conquer the hill. Within days of the St Simeon conquest, five Palestinian neighborhoods were conquered, and by 15 May, when Israel was established, southern Jerusalem was entirely in Israeli hands.

It is one thing to put in writing this counter-narrative. But how does one effectively expand the prism of a well-entrenched myth? The first strategy is making room for counter-narratives in public spaces. This particular tour was part of a three-day art intervention Here, in this no-here (the title itself is a quote from a Mahmoud Darwish poem), based on the research and creative production of Jerusalem, We Are Here. The event was co-organized with Zochrot, a non-for-profit Israeli organization that openly calls for the return of Palestinian refugees. Zochrot has a long history of making educational, artistic, and physical interventions that foreground Palestinian history. In this case, curators Debby Farber, Hagit Keysar, and myself designed very local counter-narrative interventions. The event program states:

The project seeks to reconstruct, map and document the erased historical memory of the Palestinian Katamon, and reweave relations – both imaginary and concrete – between people, homes, buildings and streets in Jerusalem’s past, present and future. The project’s centerpieces are artistic interventions in private houses in the neighborhood, which will be opened to the public, where absence and presence coexist most poignantly, and where the untold history can turn from absence into presence. The event will also include alternative tours, as well as a symposium and poetry reading concluding the three-day event.

Undoing the erasure and making present that which is absent worked organically in the intimate space of the homes of Israelis who agreed to host the Palestinian past and to be part of a conversation about the present and the future. Bringing the same goals into the tour design, I called the tour “Who heard of Semiramis?” knowing full well that most Israelis have no idea what the Semiramis was. I wanted to intrigue audiences, but also to signal to them that they would have to face a history they are not aware of.

I chose to start the tour near the modest and abstract monument commemorating the battle of St. Simeon, where I told participants the story as Abdullah al-Tel (the Jordanian commander of Jerusalem) and David Shalti’el (the Haganah, or paramilitary forces, commander of Jerusalem) would tell it. I chose to start there because this is a familiar shared myth of bravery and perseverance, and it was an opportunity to expand the story, showing Palestinian bravery, as well as the circumstances outside the control of the soldiers on the ground. I used this story as a demonstration that history is nuanced and complex, even if the way we usually experience it is partial to the teller’s position and agenda. I was not trying to replace one narrative with another, rather to provide a narrative that contains multiplicity, fissures, and contradictions. This introduction was effective in carving an intellectual space for hearing a broader narrative.

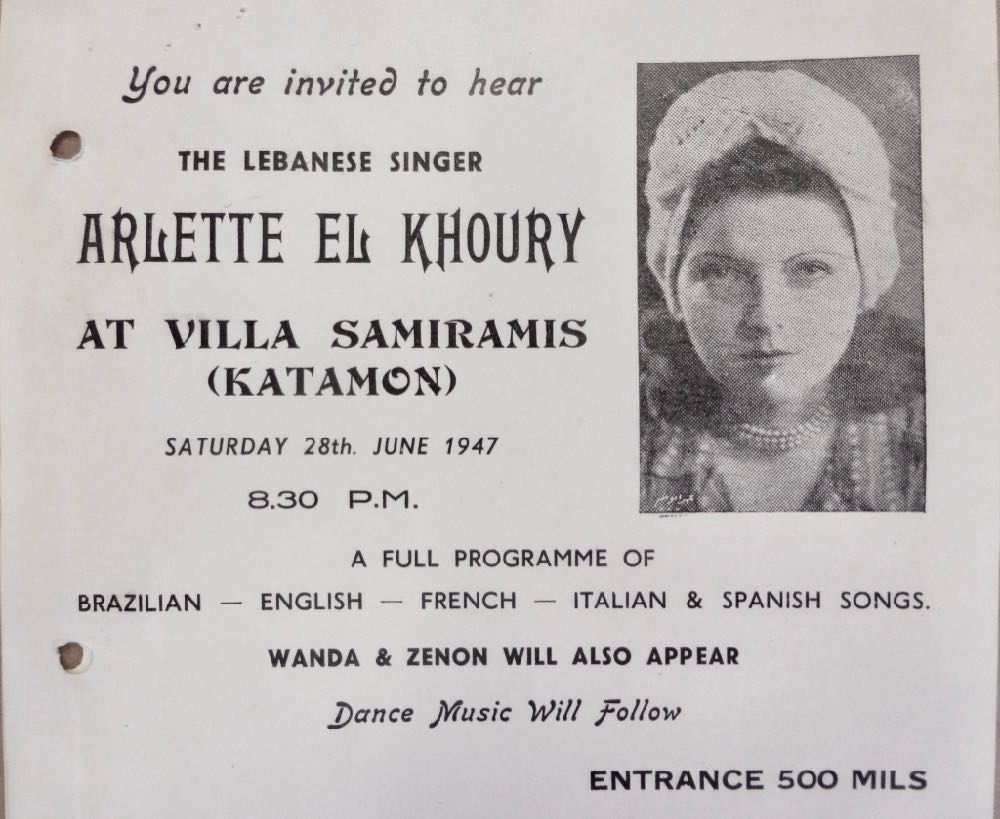

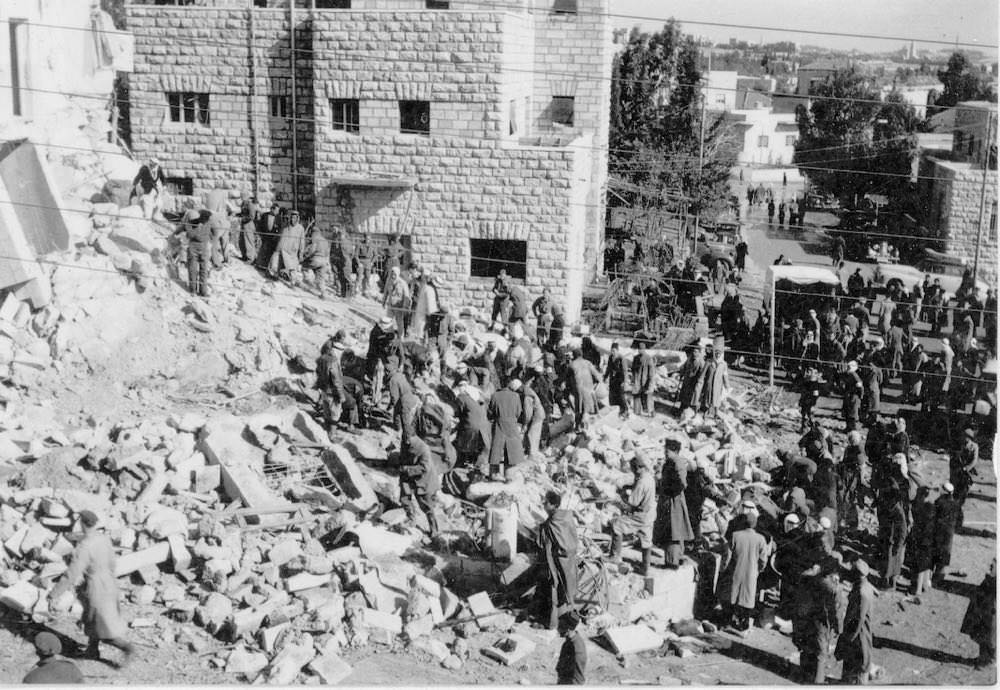

The counter-narrative came in more directly two stops later, when we stood by what used to be the Hotel Semiramis. This small family-owned hotel looms large in Palestinian consciousness, because it marks the beginning of the Nakba (Palestinian catastrophe) in Jerusalem. On 29 November 1947, the UN voted to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The British Mandate would end almost six months later (on 14 May 1948) but from this point on, warfare between Arabs and Jews raged openly. On the night between January 4 and 5 1948, the eve of the Greek Orthodox Christmas, the Haganah planted a bomb in the hotel. The bomb exploded, killing 27 civilians attending a Christmas party, and destroying half of the hotel. Following the bombing, an exodus of scared residents ensued, an exodus that ended with the conquest of the neighbourhood by Israeli forces on 2 May 1948, and with the removal of the last remaining residents into an internment camp in the nearby neighborhood of Baq’a. The Semiramis bombing still marks “the beginning of the end” for the multicultural Palestinian middle-class neighborhoods of Jerusalem. So much so that when Abbas al-Sayed, the planner of the Park hotel suicide bombing in Netanya in Passover of 2002 — in which he and 30 civilians were killed — was arrested and interrogated, he said: “This is vengeance for the Semiramis bombing.” His interrogators had no idea what he was talking about. Indeed, the Semiramis is not part of the Israeli narrative of 1948. The building itself was converted to an apartment building, and no reference to its past exists in the space.

Standing in front of the Semiramis I showed a poster for a concert at the hotel advertising Arlette El Khourri singing in “Brazillian, English, French, Italian and Spanish.”

I recounted the details of the bombing and showed pictures of search-and-rescue in the rubble. I also read from an email sent to me by Emile Jouzy, who as a child was fast asleep a couple blocks down the hill from the hotel on the night of the bombing. Emile writes:

I remember the thunder-lightning-hail-rain-wind- and then circa 1 AM waking up finding myself circa 50 cm in mid-air above my mattress. From the pressure of the blast which when taken in a straight line in the air our apartment was no more than 300 meters from the SEMIRAMIS HOTEL.

In her memoir, Jerusalem and I (1987), Hala Sakakini describes the following day:

All day long you could see people carrying their belongings and moving from their houses to safer ones in Katamon or to another quarter altogether. They reminded us of pictures we used to see of European refugees during the war [WWII]. People were simply panic stricken.

In tours I co-guided with Palestinian linguist and Jerusalem historian Anwar Ben Badis, we used a dialogic approach to similar ends, each delivering quite radically different stories, with Anwar primarily delivering specific Palestinian stories, and myself primarily Israeli ones. We used quotes, memoirs, books, poems and documents, not only as evidence, but as a polyphonic approach to multiple historical narrative. In a 2015 tour designed for a joint Palestinian and Israeli audience (a rare occurrence in itself), we decided that Anwar would speak only in Arabic, and that I would not translate, but rather deliver different information. We suggested that Israelis who don’t speak Arabic (the majority), ask a Palestinian to translate. This, alone, created an uncommon dynamic where Palestinians and Israelis mingled and talked as we walked around the neighborhood. At one street corner between the “Conquerors of Katamon” and “The 29th of November,” we pointed out that most street names in the neighborhood commemorate the 1948 conquest/victory. Interestingly, in the first few years after 1948 the streets were all named after flowers, but later were converted to more militaristic/nationalistic names. Standing at another street corner, Anwar pointed to the street name, Rahel Imenu (our mother Rachel), and called it “your mother, Rachel.” These tactics destabilize the relationship of Israelis to the space and the implicit assumption of unproblematic, or natural, sovereignty over the neighborhood. We did not replace the Israeli history with a Palestinian one, but rather wove them together to an interlaced, expansive place.

In all the tours that we guided together, or I did by myself, the most poignant moments were when we included the narratives of individuals — whether Palestinians who lost their homes, Israelis who reported or saw the looting, or poor Jewish refugees that settled in the middle class neighborhood being exposed to pianos and bathtubs for the first time, and so on. The main voice, though, was always a Palestinian voice, the one most actively and pervasively silenced in Israeli discourse. Bringing in the first-person experiences of Palestinian residents served a double purpose: on the one hand, it gave credibility and detail to the general story. But it also personalized it with names attached to feelings of fear, shock and sorrow. Such personal accounts allowed tour participants to experience empathy towards individuals, bypassing – if just for a few minutes – the binaries of us/them or Israeli/Palestinian, and thus moving towards humanism. I would argue that while humanism in and of itself is an insufficient condition to facilitate change, it is a necessary condition before any political change can be conceived. In Strange Encounters (2000), Sara Ahmed shows us how the “stranger” is constructed culturally and politically as different than us, and here I wanted to flip the script and make the stranger — for an hour or two – us. I felt strongly that empathy could be harnessed towards deep affective engagement if embodied. To that end I devised a polyvocal, participatory, and performative strategy.

Embodying the “Other”

At the beginning of the walk in May 2017 I asked for seven volunteers and handed them sealed envelopes with names handwritten on them. When we reached the (former) Kassotis house (the first stop of the tour at a private home) I asked who had the Kassotis envelope and invited the Jewish orthodox man who raised his hand to open the envelope. In it is was a letter written by Marina Parisinou, the granddaughter of Manolis Kassotis, the owner of the house. Marina wrote:

This house belonged to my grandfather who purchased it and a few years later, around 1933, moved his family in, when my mother was about three years old. Her younger sister was born in this house.

The road you’re probably standing on they called the “katifóra”. In Greek the word means downhill slope. They would go down the “katifora” and turn left at the Semiramis Hotel to go meet up with their cousins who lived several blocks away.

In early January 1948 the Semiramis was reduced to rubble following a Zionist bombing attack. Many people met their end under the pile of stones. And so did my mother’s life in her home.

Soon after the bombing, the family went down the “katifora” for what was probably the last time. They stayed at their cousins’ home which was in a somewhat safer area before leaving Jerusalem altogether hoping to return soon, in more peaceful times, not realising that instead they were becoming refugees.

The one-story house is now gone. The stones that have been placed on top of it to turn it into a three-storey apartment building have buried what my mother knew as her only childhood home. Destruction and construction: two sides of the same story of annihilation…

Marina Parisinou, May 2017

Silence.

I wait, and then from a colourful pouch hanging on me, I pull out a postcard and hand it to the man. On the one side there is a picture of Marina’s mother, Anna. On the other side, he finds the following text:

In the picture: Anna Kassotis, Al Bureij, 1946.

A girl wearing shorts, a sailor’s cap and a cigarette. I see an independent girl, flirting with the camera.

In conservative Cyprus of the 1950s there were no bicycles, short pants, or the capacity for a young woman to walk alone.

Anna built herself a life and a home, but the sparkle in her eyes was gone. The mother and aunts Marina knew were always melancholy. They were animated and lively only when they spoke of their lives in Jerusalem.

Dorit Naaman, director, Jerusalem, We Are Here

The orthodox man shows the postcard, reads the text on the back, and then we continue walking.

The same pattern repeated itself at each of the seven homes we stopped by. In this repeated structure, seven Israelis performed the first-person voice of Palestinians who lost their homes in 1948 or their descendants. In having Israelis read out loud words written by Palestinians I was trying to circumvent the current near-impossibility of face-to-face dialogue between Palestinians and Israelis. This impossibility emerges for various reasons. The first has to do with the self, and how it is structured in racially (and nationally) charged contexts. Israelis are automatically defensive about their right to the space, or about existing in Israel altogether, and thus shut the possibility of empathy, of listening to counter-narratives, and ultimately of taking on responsibility. At the same time, to ask a Palestinian to stand in front of their home and justify their right to the place (or to exist altogether) to Israeli audiences is, I feel, unethical. It would put the burden of educating Israelis, displaying the pain and loss, and at the same time calming Israeli anxieties, on the shoulders of the Palestinian. Even writing the letter to the tour participants was emotionally difficult for Marina, as she wrote to me in an email (11 May 2017):

I was ready to give up and drop you a line that I wasn’t up to it. But I saw your post on our page this afternoon and followed the Zochrot link. Seeing the way you have framed your tour – Who heard about Semiramis – inspired me to write the following.

During the years after the Oslo Accords (1993) much money, effort, and publicity was devoted to dialogue projects between Israelis and Palestinians. Listening to the “other’s” narrative was supposed to humanize the other and change the course of history. But in those same years, Israel entrenched and expanded its occupation, subjugated the Palestinian economy to the Israeli one, and designed the Palestinian Authority as a sub-contractor of Israeli agendas. Not surprisingly, Palestinians started to shy away from “dialogue” projects and in 2005 hundreds of Palestinian civil society organizations issued a call for Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS), which halted most collaborations. It would therefore be unethical and politically misguided to facilitate this physical encounter, and this is why I devised this proxy strategy with the letters.

But this proxy did more than facilitate a stand-in for the absent Palestinian body. Because it was an Israeli who delivered the Palestinian voice, the binary of either/or was transformed into an embodied narrative of “both” at the same time, both narratives despite, or because of, their contradictions and unresolved gaps and fissures. Furthermore, the Israelis listening to an Israeli orthodox man reading a direct address by a Palestinian woman were transformed from observers or bystanders to interlocutors in a dialogue. Marina starts with a direct address: “this home” and “the road you are standing on,” making the “here” and “now,” and the audience, visible and palpable. At the same time that the tour participants were progressively activated as witnesses, neighborhood residents were becoming observers. While the man was reading, orthodox families were filing out of the adjacent synagogue after the Saturday morning prayers. They would have never stopped if the person reading was secular, and coded as a leftist, but surprised by at seeing an orthodox man wearing a kippah, they stopped and listened. At the Farraj house, an ultra-orthodox family came out to the second-floor balcony and listened as a letter from Johnny Farraj to the owners of the house was read out loud in Hebrew. One (small) positive result of this structure/performance was that at no point were slurs hurled at the tour participants.

From Observer to Witness

Importantly, embodying the Palestinian voice was nestled into another performative interaction, this one emphasizing the Israeli present tense. Tour participants also read aloud from my words about how I met those people, what I saw in the pictures, and how I felt. The seven Israelis performed my perspective, that of an Israeli individual who for the previous ten years had engaged with the Palestinians who lost their homes and way of life in Palestine. For the duration of the project I was burdened by the responsibility to carry these stories, and to document and impart them with care. I became not only a witness, but a human archive, a resource for other researchers in the area, architects working on preservation assessments, artists and activists. Especially with Israelis, I did not want to be a service provider, enabling passive consumption of this sensitive and fraught “data.” I wanted those who received information to become actively responsible for this information. In the tour I felt strongly that my role was more expansive than education alone; I was probing a personal and active engagement. In the context of the tour I wanted participants to be witnesses, to be part of the physical “scene,” with all the ethical weight of that position. By handing out the postcards with my first-person perspective I invited the Israeli participants to consider the effects not only of the life lived, and the loss, but also the burden of sharing these stories. At the last stop of the tour, standing in front of the Louisidis house at Abdin square, I announced:

I have become a human archive, a witness to much misery I am implicated in, despite being born many years after the 1948 war. I have more postcards to give away, but not enough for everyone, and if you choose to take one, I ask you to take it with a commitment to ask yourself honestly: ‘What is my responsibility?’ I am handing out postcards as invitations to be witnesses alongside me, to share my burden, to study this history, which is also our history, and to commit to actions that will bring forth conciliation.

Tour participants fought over the postcards.

Later I heard independently about tour participants who reported that the tour was excellent because it invited them to take responsibility without making them feel guilty. Redirecting responsibility away from solipsistic white guilt is no small feat, and these comments were an amazing reward.

When designing the tour, I considered turning it more towards a performative act, asking people to pin the postcards and letters to my own shirt, making visible my body as a growing archive of Palestinian loss. But in the end, I decided to “wear” my responsibility more implicitly, and to nudge tour participants towards wearing theirs too. A few participants in tours over the years told me that when they now walk the neighborhood they see it differently, experience its ghosts and fissures, and think about the past and the future as they walk. Like the excited woman who heard Arabic poetry not far from her home for the first time, these people’s neighborhood has changed and echoes the tours. In the end, the process has to start with individual accountability, but until “we” (Israelis) “wear” our responsibility as a society, we are likely to stay caught in the (neo)liberal discourse that personal recognition, acknowledgement, or even an apology equals reconciliation. Walking tours such as the ones conducted as part of Jerusalem, We Are Here start the process of unsettling the relationship to familiar spaces, by providing a more expansive, embodied and affective understanding, and encouraging new place-making, inclusive and responsible.

I am crying as I write this. I was born and lived in Katamon. Khalil Sakakini is my great uncle. We lived in an apt. in the same building where Abu Samir, Awad Fataleh’s grocery store was. I was there as a child when Samiramis was bombed. The trauma of this bomb that woke us up and terrified us can never be forgotten. That and the King David rubble still haunt me. I mention that in my memoir which I hope to publish soon.

I wish I can join a walking tour in Katamon sometime before I get too old.