Introduction

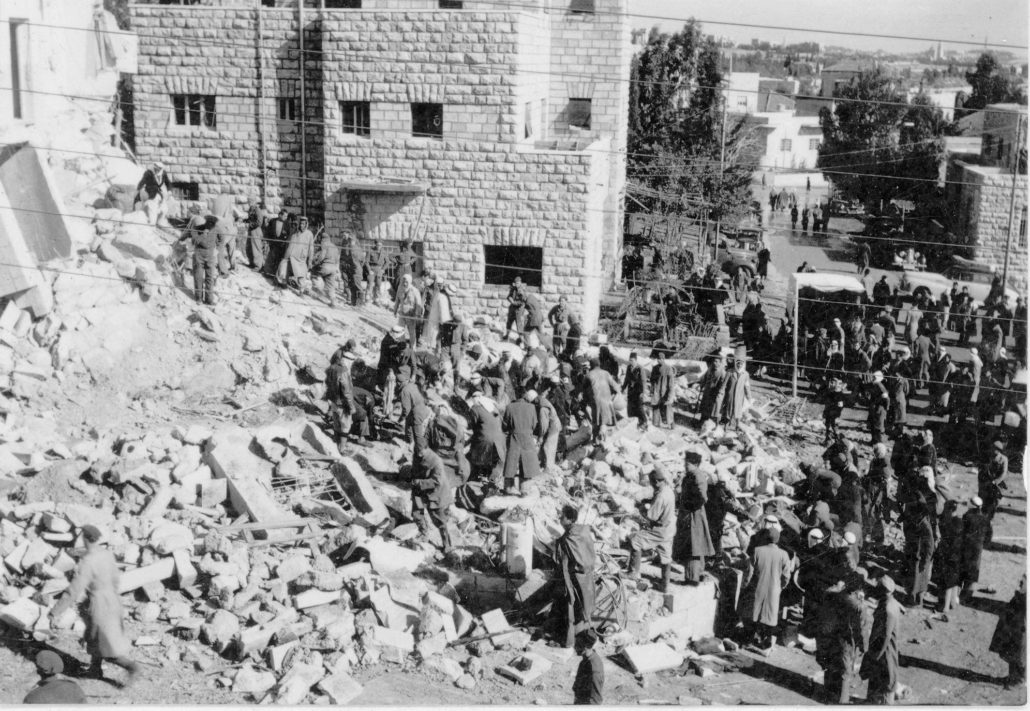

“Hearing Arabic in these streets and hearing about the people who lived here gives me double vision,” an Israeli woman told me emphatically. “I grew up in Katamon, and the Palestinian past of this neighborhood was never part of my landscape. I can promise you that I will never walk these streets in the same way!” she proclaimed. The woman was attending a guided walk, one of half-a-dozen public walks I guided or co-guided while doing research for, and production and dissemination of, Jerusalem, We Are Here, an online project designed with Palestinian and international audiences in mind. But as an Israeli engaged with uncovering a buried Palestinian past, I wanted to reach Israeli audiences as well. The engagement in the space had various manifestations, with public guided tours being an evolving core. The design of the tours was organic and intuitive, but my goal was to use them as an experiential and structured vehicle for considering not only the Palestinian past, but also the future, and Israeli responsibilities towards that future.

In a fraught political space with active and continuous forms of erasure and exile, walking, by itself, does not have the capacity to reveal entanglements or remake place. I first started learning the Palestinian history of the neighborhood from Ghada Karmi’s memoir “In Search of Fatima” and Khalil al Sakakini’s diaries. But as I physically walked Katamon, I had no anchors to any of the landmarks mentioned in the books. Even former public institutions do not have plaques identifying them, let alone individual houses. While most Israelis know they are walking in a former middle-class Palestinian neighborhood, the large Israeli flags, welded iron Star of David or Menorahs on gates and fences, and the street names, all work to suppress the Palestinian history. As a tour guide, if I wanted to activate not only an expanded understanding of the past, but also an implied present and imagined future, I would have to first unravel Israelis’ well-knitted narratives. In effect, I was working – gently – to “unsettle” Israelis.

Read more