On the “Here” in Jerusalem, We Are Here

In 2007 I rented an apartment in Katamon for a six-month sabbatical from my university in Canada. I grew up in a different part of Israeli Jerusalem, but my parents had moved to a new development in Katamon (over the old soccer field), and as I had a one-year old baby, I wanted to be close to them. When I arrived, I could tell that the house I rented had been built before 1948 in the International architectural style common in the 1930s-40s. The staircase exuded spaciousness, but the apartment itself was small and entirely remodelled. In fact, what was once a two-family duplex, was now subdivided into seven or eight apartments.

I knew very little about Katamon, but I did know that it was Palestinian before 1948. A few years earlier I read Ghada Karmi’s memoir In Search of Fatima and while the book left a deep impression on me, her Katamon and the one I was wandering with a stroller in tow did not quite align. For one thing, there were no markers for any of the landmarks, such as the Semiramis or Bellevue family-owned hotels, the Lebanese and Iraqi consulates, or the perimeters of security zone A, which the British set up when the “troubles” (to use an imperial euphemism) started. How could I find out where those places were?

One day, I saw a walking tour stop by the house next door, a modest single-storey house with a red-tile roof. The house was divided between a Jewish-Arab family and a daycare centre (ironically sponsored by a Canadian Haddassa -Wizo chapter). A few days later, I saw an article in the newspaper Ha’aretz about Palestinian homes in West Jerusalem, and lo and behold there was a picture of the house next door.

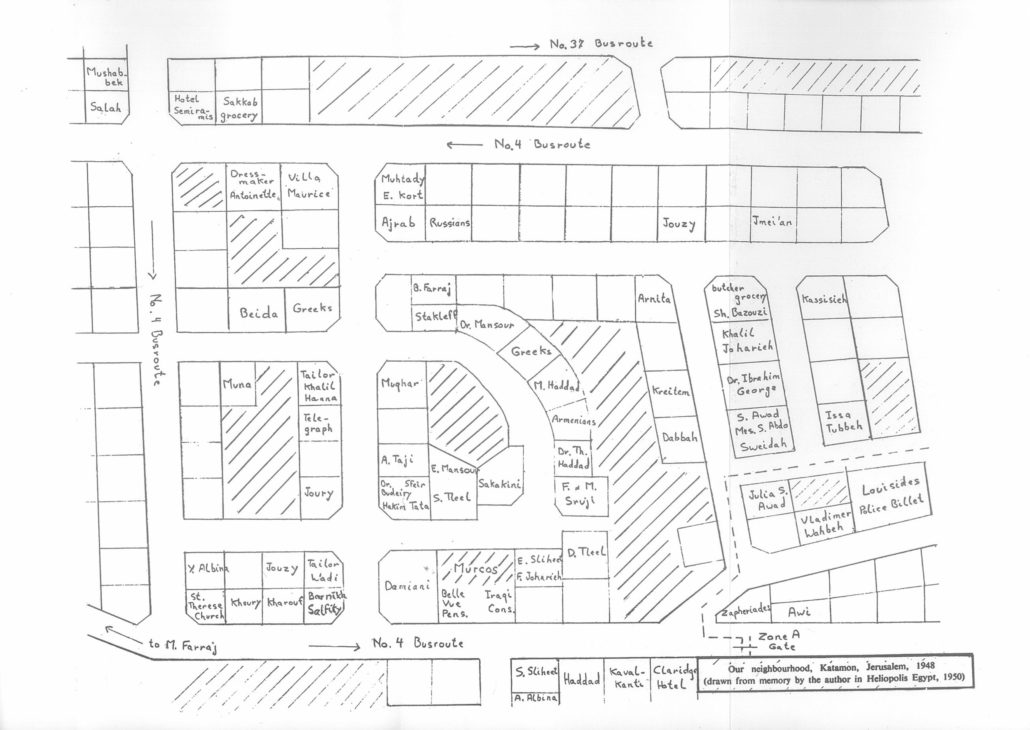

It turned out the house was built by the famous Palestinian intellectual Khalil al-Sakakini, whose diaries (actually a small selection of) have been translated into Hebrew. I gobbled the book up, marvelling at the poetic writing style, proto-feminist ideas, advanced pedagogical principles, and political acumen. Now I knew a lot more about the neighborhood and life for middle-class Palestinians before 1948. But I was frustrated; Sakakini was famous, and so we know where he lived. But what about the house I lived in? So what if the owners were not famous? Should they recede from history? Slowly but surely, I was abandoning my sabbatical project, and started researching the history of the neighborhood. I knew that Sakakini’s daughter, Hala, published a memoir, but it was out of print. Then, by a fluke, I found a copy at the Jewish National book archive at Hebrew University. Hala’s memoir, Jerusalem and I, provided a lot of information about the residents of the neighborhood, and also contained a treasure: a hand-drawn map which she constructed from memory in 1951 while in exile in Egypt.

Now I knew that I was living in Suleiman Tlil’s house. I was not comfortable imagining the Tlils carrying their loss over the years, while I could easily rent their apartment, but pay the rent to an American Jewish family that now owned it. I did not know anything about the family, but I put a little sticker on my mailbox with the name Tlil. It was a silly gesture, private and insignificant, but it gave me pause every time I picked up the mail. Ideally, I would have liked to mark the house somehow, like the stolpersteine in Germany – plaque-covered cobblestones bearing the names of victims of Nazism who lived or worked in the buildings next to the marker. But I did not own the house, and, in the ever more racist Israeli climate, it was difficult to imagine such a marker not vandalised. And besides, marking and memorializing (just like acknowledging indigenous land in North America) is important in changing consciousness, but is not an end in and of itself. I was worried that acknowledging the Palestinian rightful owners would allow Israelis to recognize the past, without having to do anything about remedying its consequences.

Instead, I made a short film called Two Houses and a Longing about the Sakakini house and the Baramki house (in Musrara), and in the video I played with signage. I closed the video with a graphic superimposition on the Sakakini house, acknowledging his ownership and posing a question to the Israeli audience about the need to deal with this past in order to have a future. I felt that art could transcend entrenched positions and open doors to consider politics from a fresh angle.

Then I came up with an idea to look for the families shown on Hala Sakakini’s map, and to make short films with them. My initial impetus was to work with the Israelis who lived in the houses now, and make short films with them, too. I planned to project the films on the houses in an installation and was hoping it would spark an organic communal discussion about Israeli responsibility and obligation. I received a grant from the Canadian federal government and set out to find participants. But I was worried about the project falling into the “dialogue” paradigm, a post Oslo accord industry of sorts, where Israelis and Palestinians are brought into a conversation, where both sides listen to each other. While leading to empathy on an inter-personal basis, the dialogue projects by and-large avoided political analysis of the power imbalances between occupier and occupied. The dialogue projects were in full swing in the 1990s and 2000s, while the occupation of the West Bank was becoming entrenched, with the settlements doubling in size, the Apartheid Wall being erected, and the possibility of a peaceful agreement diminishing. In a sense ,the “dialogue” industry was a “fig leaf” for the occupation. I did not want to fall into this trap and was committed to not equate the Palestinian and Israeli experiences, and was particularly worried about the Ashkenazi Israelis falling into the narrative of loss of their homes in Europe. In addition, as an Israeli working with Palestinians who lost their homes in 1948 I was reluctant to ask the Palestinian participants to share their pain and loss only in order to educate Israelis. I wanted to create a platform that would serve the diasporic Palestinian community of southern Jerusalem. Eventually, our team developed the concept for Jerusalem, We Are Here: an online platform that allows any Palestinian virtual access to Jerusalem, with no checkpoints, surveillance, or intimidation; and an online organic map where in collaboration with the community we continue to identify the owners of the houses in the neighborhood.

Between 2013-2016 I spent much time in Jerusalem, collecting archival material, filming, mapping, and developing the content and form of the documentary. In those years I was careful to rent houses that were built after 1948. Not that this gesture absolved me of benefiting from the results of the 1948 war, but at least I was not actively participating in dispossession. Over the years I heard about a couple of Israeli families who tracked down the Palestinian owners of their houses, and bought the house – a second time– at full current value. But I have not met these people and am not sure if this is not an urban myth.

However, it seems as if the issue is bubbling up to the surface. In May 2017, to commemorate the 69th anniversary of the Nakba, I collaborated with the Israeli organization Zochrot in a three-day event in the neighborhood. Three families opened their doors to us, where we installed parts of the project. One of the current owners told me the day of the opening: “I keep thinking, what if a Palestinian woman walks in and tells me it is her house. What will I do? I guess we’ll have to go to a lawyer and sort it out.“ But the anxiety did not stop her from hosting the exhibition, and explaining time and again to Israelis why she was willing to host the Palestinian story in her home. We led walking tours in Arabic and Hebrew, and organized a symposium with Arabic and Hebrew poetry, as well as more academic presentations. To my surprise, hundreds of Israelis showed up, many of whom were local residents who were eager to know who owned their houses. What they did with that information is difficult to say, but clearly, a new awareness was murmuring in the neighborhood. At the end of a tour I guided, I offered the ninety participants postcards that I prepared in advance, with pictures of Palestinian owners and messages from them to the Israeli tour participants. As I handed the postcards I told the crowd: “By taking one of these I invite you to share with me the burden of witnessing the results of the Palestinian Nakba, and I invite you to ask yourselves, what is our responsibility?”

In April 2017, I was co-presenting the project at the Jerusalem Fund in Washington D.C. My co-presenter was Jamil Toubbeh, who had flown from Albuquerque, New Mexico, to be at the presentation of Jerusalem, We Are Here. Jamil was born in Katamon in 1930 and had published a memoir called Day of the Long Night: A Palestinian Refugee Remembers the Nakba. He is the uncle of Michel Moushabeck, who participated in the project, and over the years has provided much valuable information. With a crisp memory, Jamil would help me identify a house by sending me an email with precise directions that started at the last stop of bus #4 (which I could find on Hala Sakakini’s map), and continued with an exact mental map of the streets. But I did not meet him in person until Washington D.C. The night before the screening we were seated at a nice restaurant, overlooking the Potomac River, with Layla, a lovely young student at Georgetown, and an intern at the Jerusalem Fund who came to interview me, and then joined for dinner. Jamil asked Layla: “When did you leave Gaza?” Not missing a beat, with a beautiful broad smile, she replied: “I never left Gaza.” Indeed, in my experience, most Palestinians in the diaspora have never truly left their homes.

The next day we stood together, Jamil and I, in front of the screen on which Katamon was projected, and he asked me to “walk” from Spinney’s (a deli in the German Colony), to the Toubbeh house (which no longer exists), over to the Sakkab grocery store and on and on. The stories flowed, and everyone was rapt. I saw two sisters weeping, and at the end of the presentation they came and told me:

“We went to Jerusalem three times with our father’s instructions and could not find his house. Now you were scanning over it, and we finally know where it was. Our father is no longer alive to see his house, even if on a screen.”

The war and the inability to return, even for a visit, is a barrier to knowledge, but not to emotional attachment. At a certain moment Jamil faced the audience and said, pointing at the screen:

“This proves that we exist, that we are from Jerusalem, that we are real.”

For me, Jerusalem, We Are Here certainly makes that assertion, but I have hopes it will also affect the way Israelis who live in Katamon see it and their own relationship and responsibilities to its fraught history.

28-5-18 DORIT HALLO just read the above and am surprised why there was no mention of the great contributions and efforts of MONA also no mention SABA OR EMILE in your great story

Dear Emile,

Yes, you are right, of course. This first post was focused on my journey, something that is not in the project itself, but that I am asked about every time I present. In future posts I will discuss various aspects of the process, including your and Saba’s contributions to the map. Another post (or posts) will describe the core team: Anwar, Mona, Marina and Livia, and how working together has shaped this project. If you would like to contribute a blog post about your memories from Katamon, we would welcome that too… Dorit