The Beginning of the End

This was first published on the author’s personal blog on 5 Jan 2018

– the 70th anniversary of the bombing of the Semiramis.

It was a dark and stormy night. No, it truly was! “Torrential rain, accompanied by thunder and lightning fell in Jerusalem all Sunday night“, wrote The Palestine Post on 6 Jan 1948 noting that the belfry of the Dormition Abbey had been struck by lightning and windows had been broken. “Throughout the night there was heavy rain and one thunder-clap at 3.50 a.m. awakened many persons in all parts of the city.“

Like in most of the neighbourhood, in a corner stone house in upper Katamon, only a few blocks away from the monastery and church of St Simeon, the Kassotis family – my mother (just a week short of her 18th birthday), her parents and two sisters – would have been awoken much earlier, had the storm allowed them to sleep in the first place. To begin with there was the sound of grenade for at 1 am on Monday, 5 January, 1948 – exactly 70 years ago – the Hotel Semiramis, two doors down the street from the Kassotis, came under attack by the Haganah, the Jewish militia.

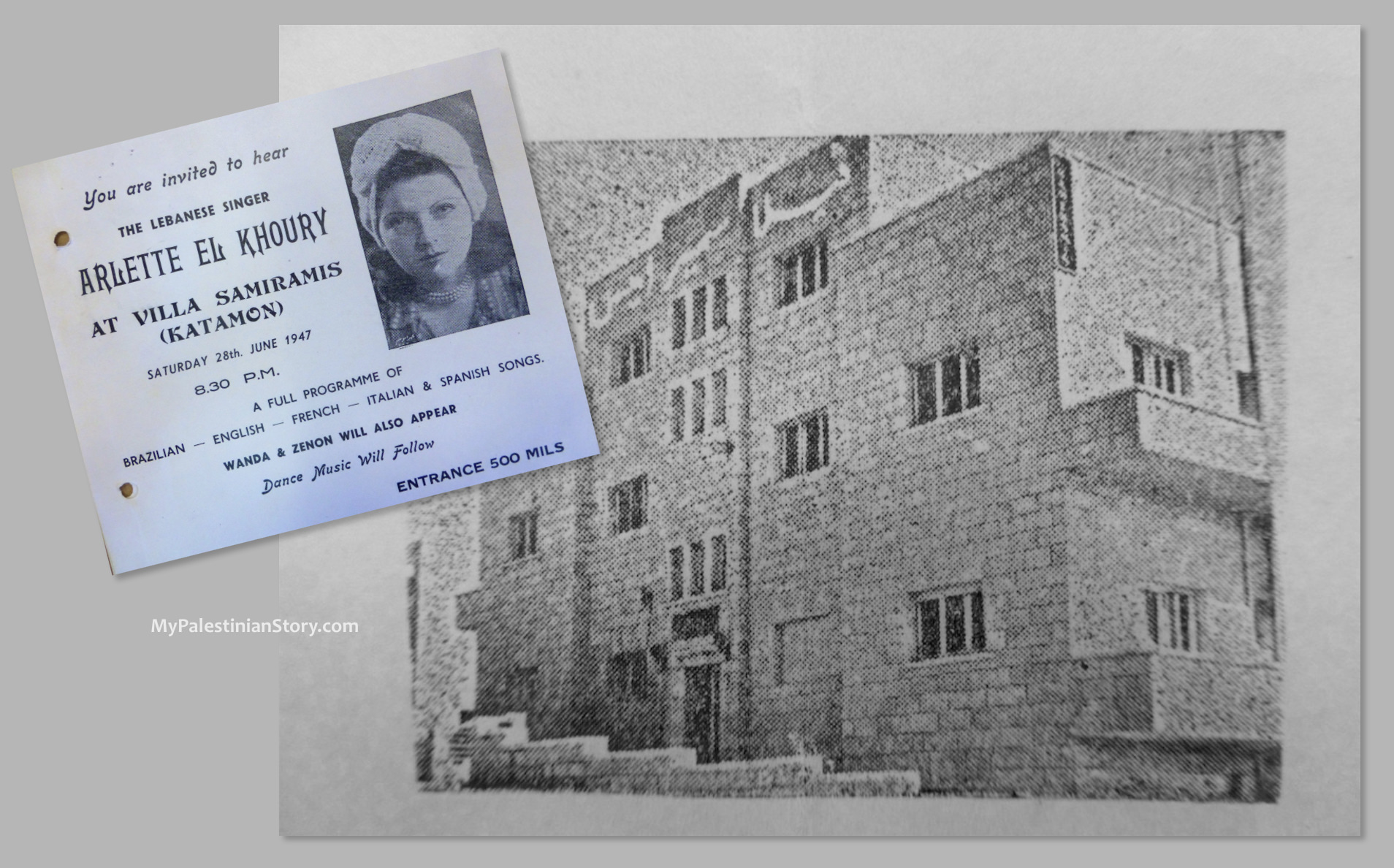

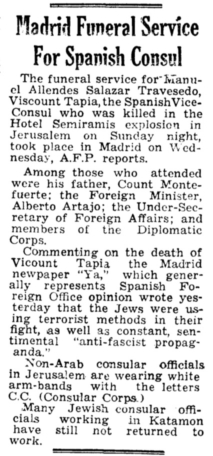

The Semiramis was a small hotel owned and operated by two Arab Christian families, the Lorenzos and Abu Suwans. The storm had knocked out the power and by midnight on Sunday, the hotel’s residents, some of them having dined by candlelight, had retired to their rooms. The Spanish Vice Consul, Manuel Allende Salazar, who was staying at the hotel, had gone upstairs to his room earlier.

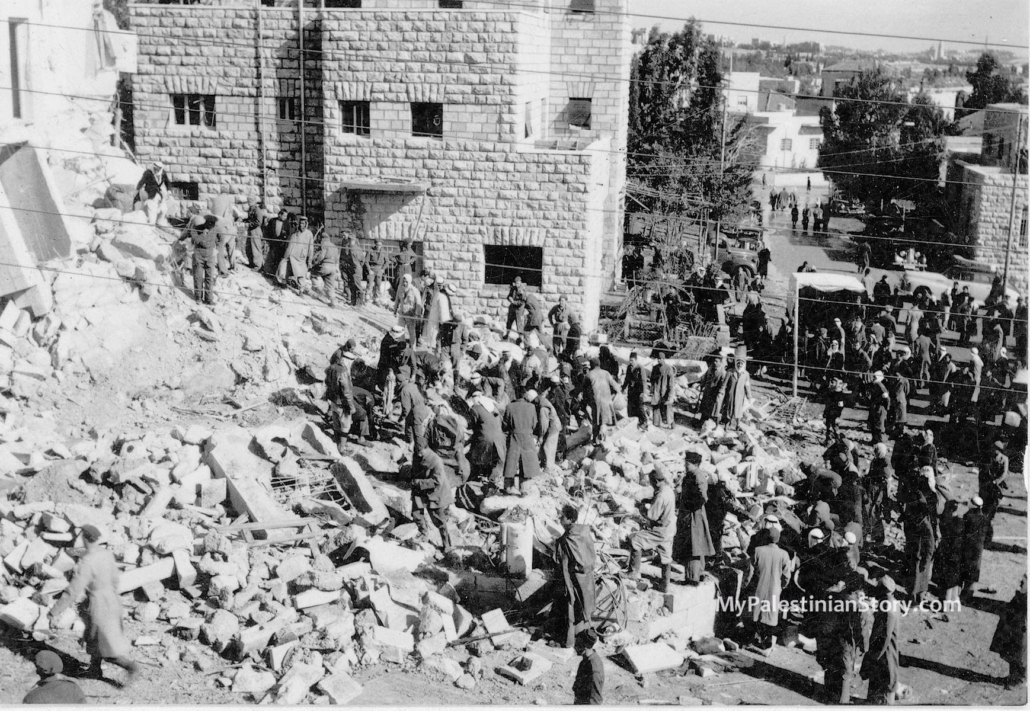

In the streets, not a soul around. Confident that the storm would deter any Jewish attacks like the ones Katamon had experienced previously, the typically 30-strong ragtag Arab guard that manned ten checkpoints by midnight was down to eight. One of them would have been the 23-year-old son of the hotel’s owner but his mother had kicked up a fuss and refused to let him go out in the foul weather. And so, the two cars carrying the Haganah operatives arrived at the hotel unhindered. The grenade gained them access to the cellar where two bags of TNT were planted and exploded a few minutes later. “The whole front of the two-storey building was blown into a mass of powdery rubble.” (The Palestine Post, 6 Jan 1948)

“The explosion illuminated the sky above the neighborhood for several minutes and shook the walls of houses hundreds of meters away. Frightened residents leaped out of bed and rushed to find shelter in the lower regions of their homes. Some residents close to the site of the explosion went into shock,” writes Itamar Radai in Qatamon, 1948: The Fall of a Neighborhood.

I was in my twenties when my Palestinian grandmother, Yiayia Vitsa, recounted the incident. I had just started reading O Jerusalem by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre and had asked her what it was like to have lived through those days. She told me about the bombing of the Semiramis and how the dog of the Spanish Vice-Consul refused to leave the ruins until the body of his master was recovered three days after the blast. Going back to the book, I read about that exact incident.

Twenty-six people lost their lives at the Semiramis. Digging through the rubble for survivors took days. The Abu Suwan family was practically wiped out with only one survivor. Hubert Lorenzo, whose mother refused to let him go on guard duty, was killed along with his parents and other members of the extended Lorenzo family. On the Wednesday, Royal Engineers rescued a woman trapped by fallen masonry.

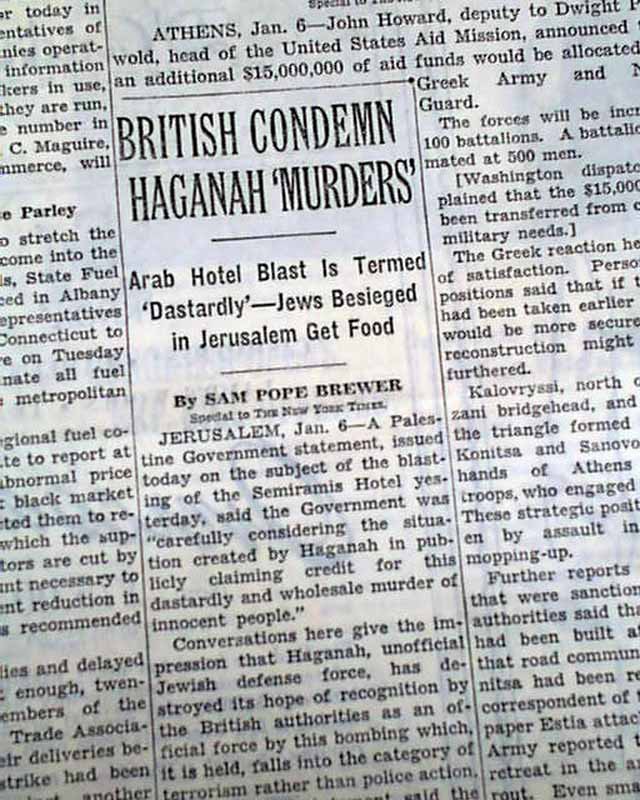

The Haganah claimed, either due to faulty intelligence or as an excuse, that the hotel served as the base for the local Arab militia, a fact which was refuted by the British administration which condemned the attack. The Jewish Agency “deeply” regretted “the loss of innocent lives.”

In addition to the dead and wounded, other lives were altered forever by this incident which helped Haganah achieve its ultimate goal: Intimidation forced people out of Katamon in droves.

Writes Radai: “The blowing up of the Hotel Semiramis was the most extreme in an unfolding sequence of events that made normal civilian life in Qatamon increasingly difficult to maintain. The exchanges of sniper fire between the Arab and Jewish neighborhoods made travel to work or shopping in the city center or in the Old City dangerous, and sometimes the road would be cut off. Similarly, deteriorating security meant that agricultural produce was no longer being delivered. …. The anxiety felt by all the children in Qatamon was further heightened after they were forbidden to leave their homes and when government schools did not reopen after the New Year holiday.“

The Kassotis eventually joined the exodus. Very few people were left at their end of Katamon which made them feel unsafe so not long after that fateful day, they moved in with the Gaitanopoulos, the family of Yiayia Vitsa’s sister, Nouna Marika, who lived in lower Katamon, within one of the security zones set up by the British. Efthymios, Marika’s husband, had already made arrangements to leave Jerusalem having secured a job transfer to Cairo, leaving the Kassotis in their house. In a few months they, too, would be forced out of Jerusalem – forever – leaving the house in Katamon and most of their belongings behind.

Unlike the King David Hotel which preceded it in the list of bombed sites (bombed in July 1946 but restored and in operation to this day), the Semiramis has all but disappeared from the memory of present-day Jerusalem. In 1986 when I visited the city for the the first time, with my mother, we thought it would serve as a good reference point to help us find our house in an area that had been completely Judaised with all street names changed to Hebrew. However, it proved to be an obsolete and unhelpful reference.

The cabbie we hailed was a handsome young Isreali Jew with a good sense of humour. When mum said her house was two doors up from the Semiramis Hotel, the driver winked at me in the rear view mirror and turned it into a joke as if she was a crazy old woman chasing a figment of her imagination. It was done tastefully and not disrespectfully (I chose to see it as flirting – with me!) and we all had a good laugh – but the challenge remained. Somehow in the course of the conversation the Greek Consulate came up so we made for that. It now occupied the building where the Egyptian consulate was housed in 1948 and mum knew that. Problem solved! Once we got there, mum provided directions: go down this road, turn here, turn there and voilà! There were the ruins of the Semiramis.

The rubble had been cleared but that part of the plot remained empty. Mum told me again the story of how it was bombed, pointed at the house across the street where the Lorenzos lived, and at the katifora (the downhill road) leading to the Gaitanopoulos’ house where they had taken refuge.

When I returned in 2014, the structure had been rebuilt but appeared to be emtpy and it remained so until last year. For Israelis, it’s just another building in what today is referred to as West Jerusalem. But for the Jerusalemites of Katamon who lived through those days, the name Semiramis will forever be associated with the beginning of the end of their lives in their beloved city.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!