Expanding the Map

To ask for a map is to say, “Tell me a story”

— Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer

by Peter Turchi

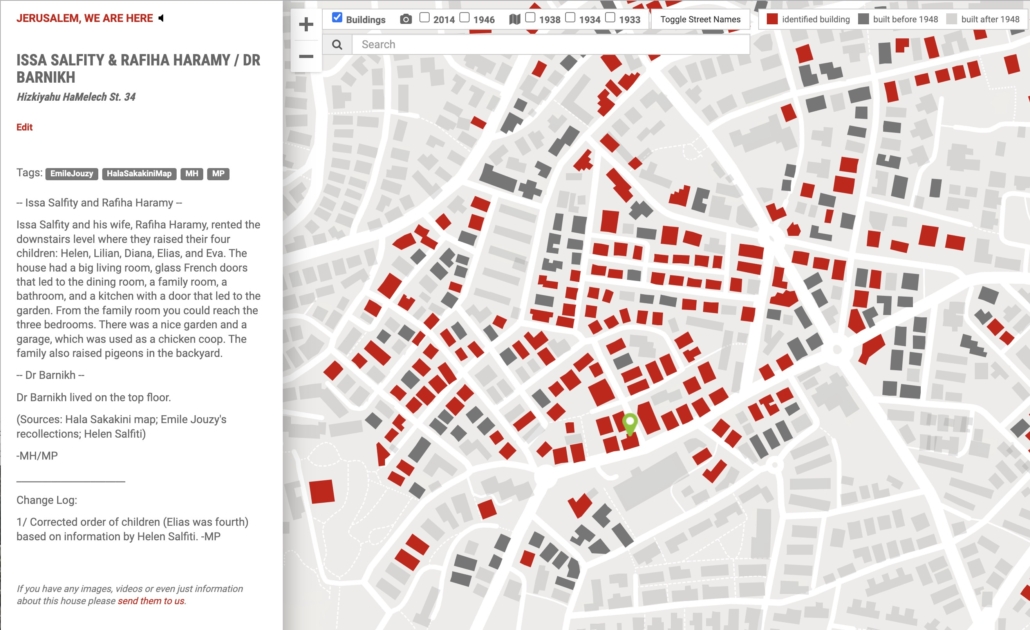

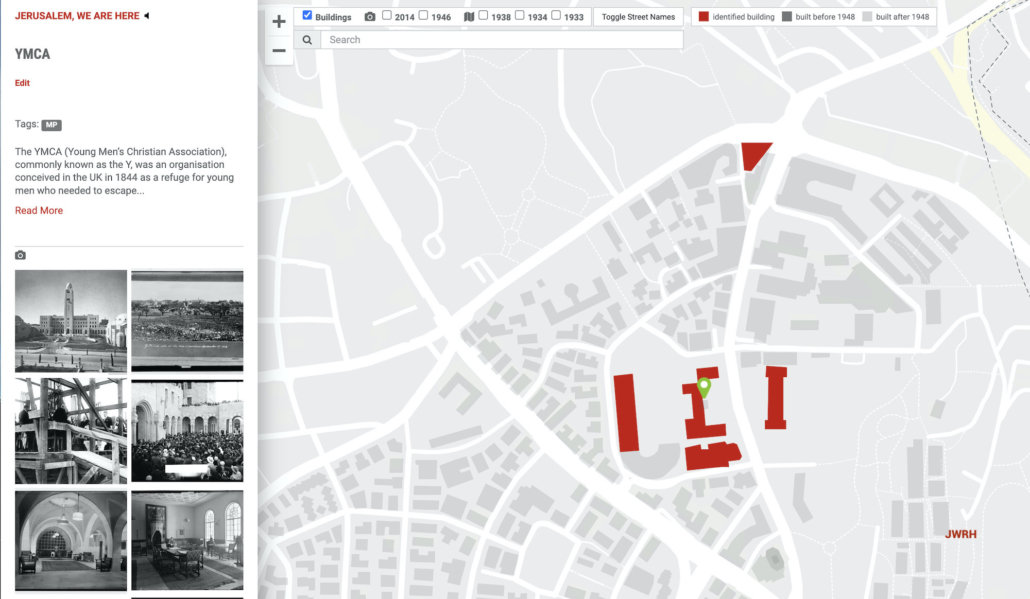

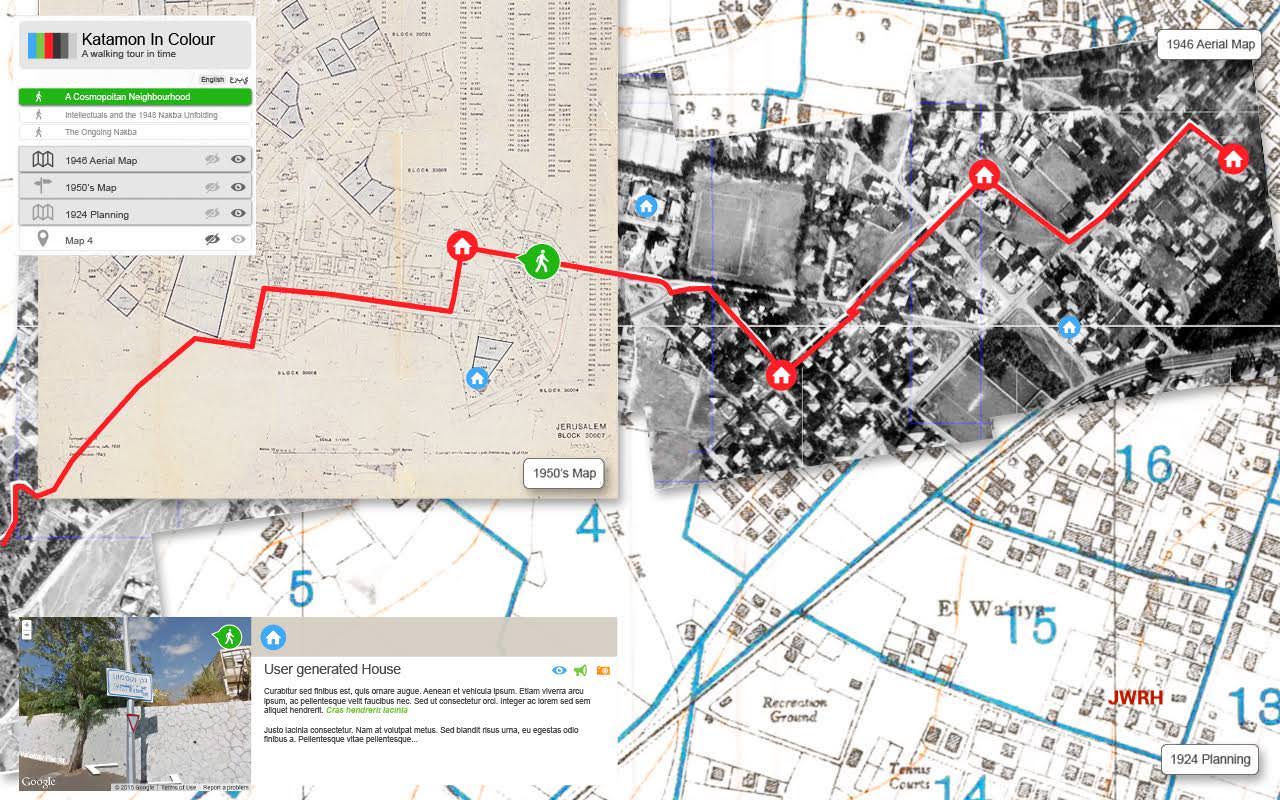

There are two parts to the Jerusalem, We Are Here (JWRH) interactive documentary: the tours and the map. The tours are, true to their name, guided tours of Katamon. The visitors select the Green, Red, or Yellow tour which they then follow on a walk along the streets of the neighbourhood (by means of Google Maps) while listening to narration. There are stops along the way—the houses of the participants or historical locations—where they can watch videos, listen to audio, or read about a place or person.

Just like the tours, the map of JWRH tells a story—many stories, in fact. It tells of the people who lived, worked, and played in Katamon and beyond, before they were scattered by the winds of the 1948 war to different parts of the world. Each house, each building contains one or more stories, one or more testaments to the life that was. Unlike official maps which are typically created by states using scientific measuring tools, our map has been developed organically, from the ground up, with the collective memory as its main resource, and stands contrary to the official story.

This blog post traces how the map was created and evolved. It also announces a significant expansion which is under way, thanks to the generous financial support of Tony Mansour and his family.

Creating the Map

Also like the tours, the map is a collaborative project—perhaps even more so. It has sprouted from the minds and work of a few, and as it grows it draws in more and more contributors.

The seed was a Google map on which Mona Halaby would place pins on houses she had identified through her interviews with family and friends. An amateur social historian (and professional educator at the time, now retired) Mona had worked on her own for years, gathering stories and photos about the Jerusalemites of her mother’s milieu, in the process of writing a book about her mother. In 2006 she was in Jerusalem for three months and in her chats with a family friend expressed the desire to see where all these people that she was learning about had lived. “Jack Said is just the person,” her friend said. So Mona was introduced to Jack and his wife, Edith, who took the time to drive her around the streets of Baq’a and point at houses. Mona made notes and then started tracking the houses on her Google map.

The vision came from Dorit Naaman, the creator of JWRH: upon meeting Mona and seeing her Google map and the wealth of knowledge she had accumulated, she was inspired to incorporate into the project an interactive map. She wanted it to be open to the community and its contributions, and thus to collaboration, allowing the knowledge to be shared and expanded.

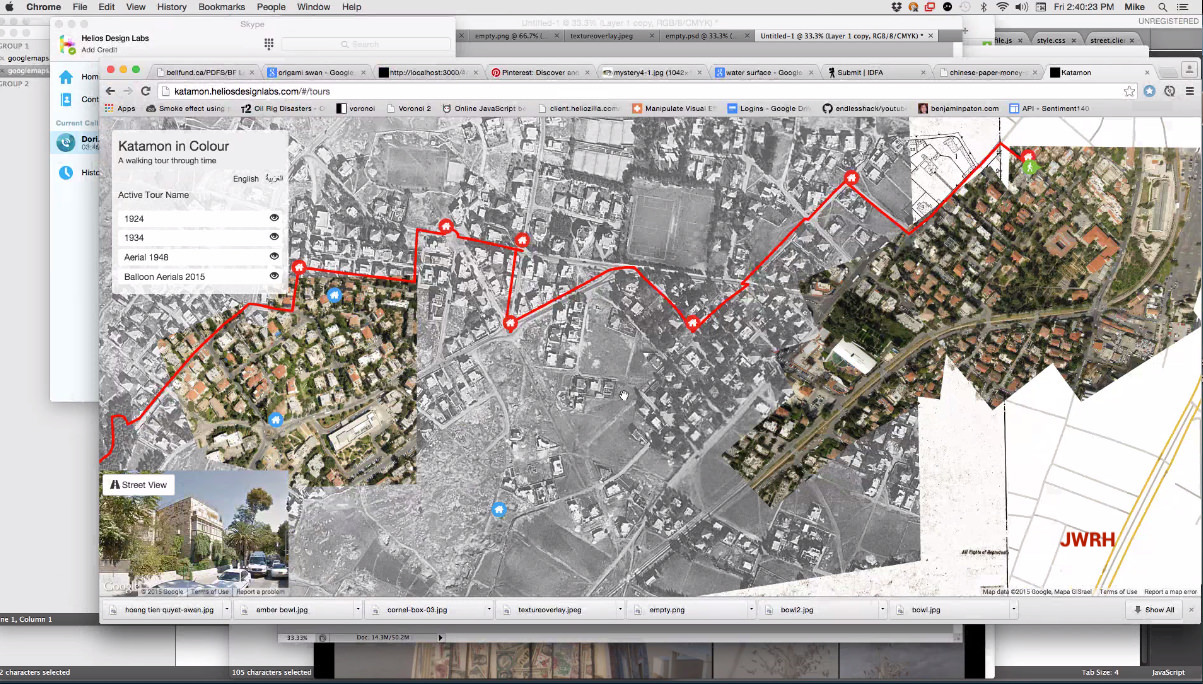

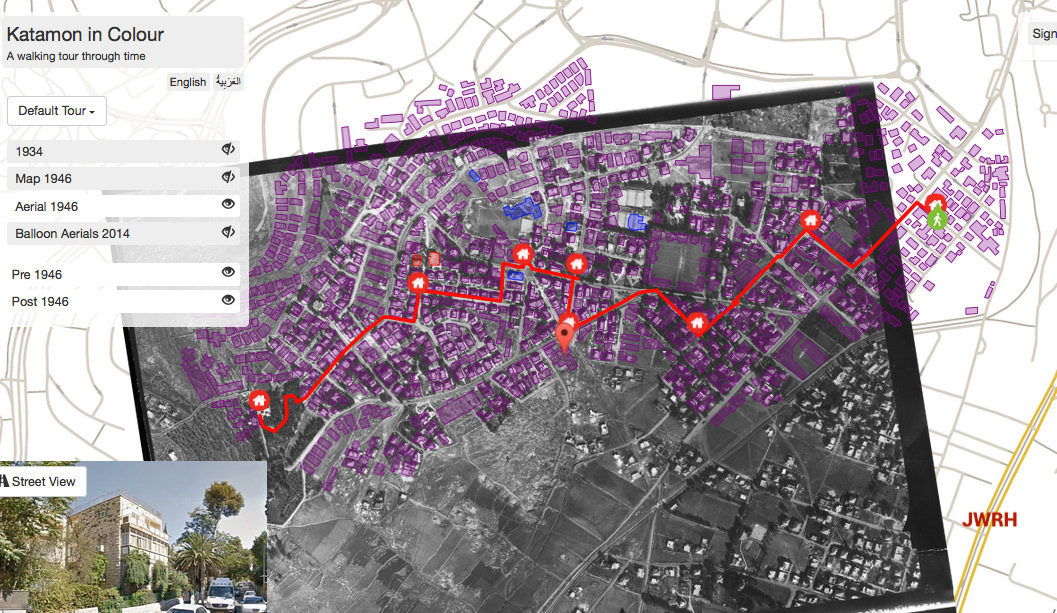

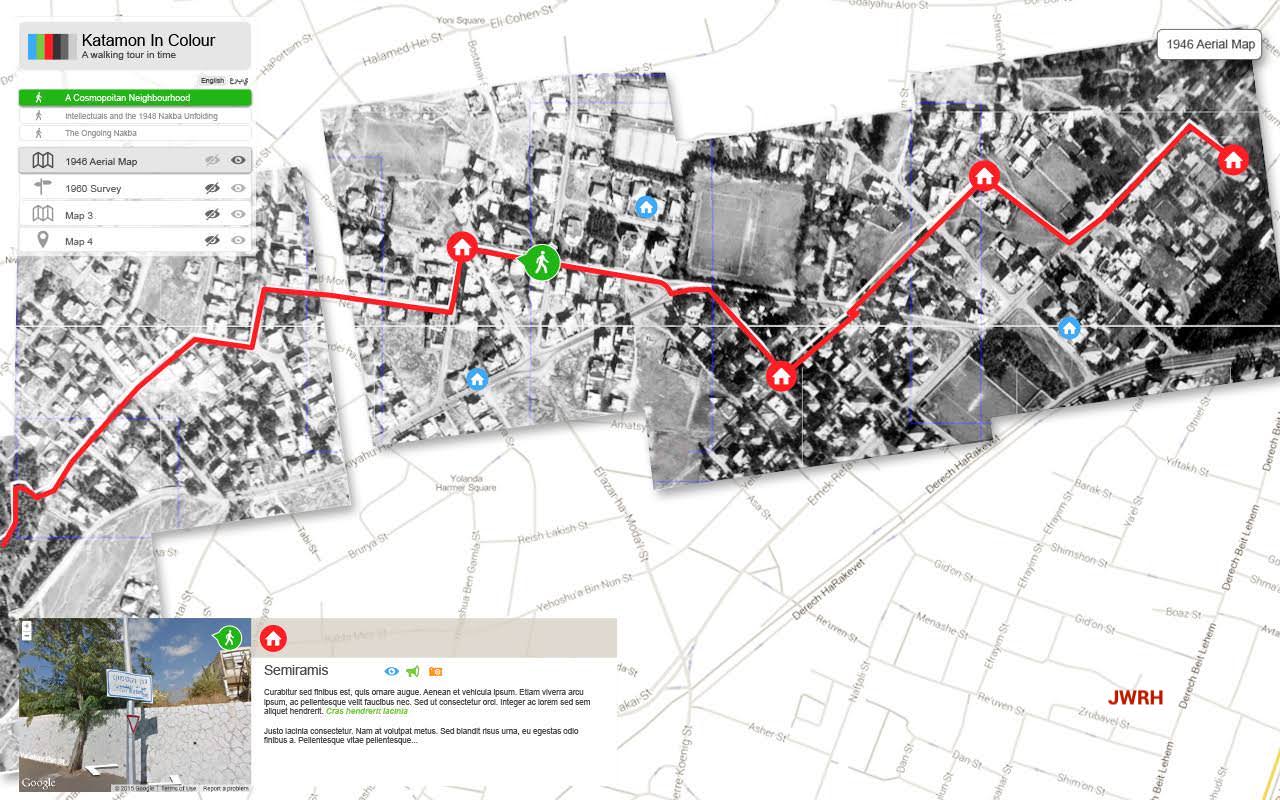

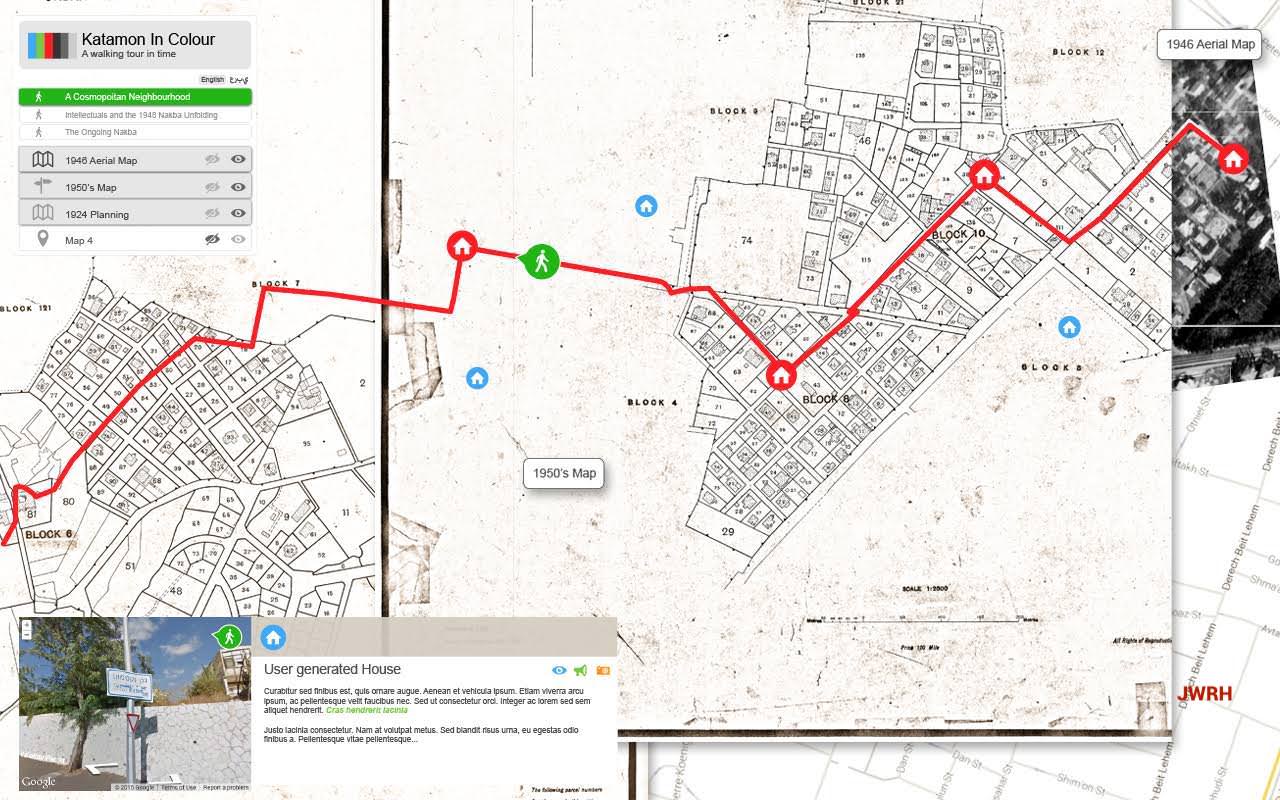

The technology was provided by Helios Design Labs, the company with which Dorit worked to design and build JWRH, and who also became associate producers of the project. They developed a unique platform on which every house in Katamon that pre-dated the Nakba became a live link and a receptacle of information.

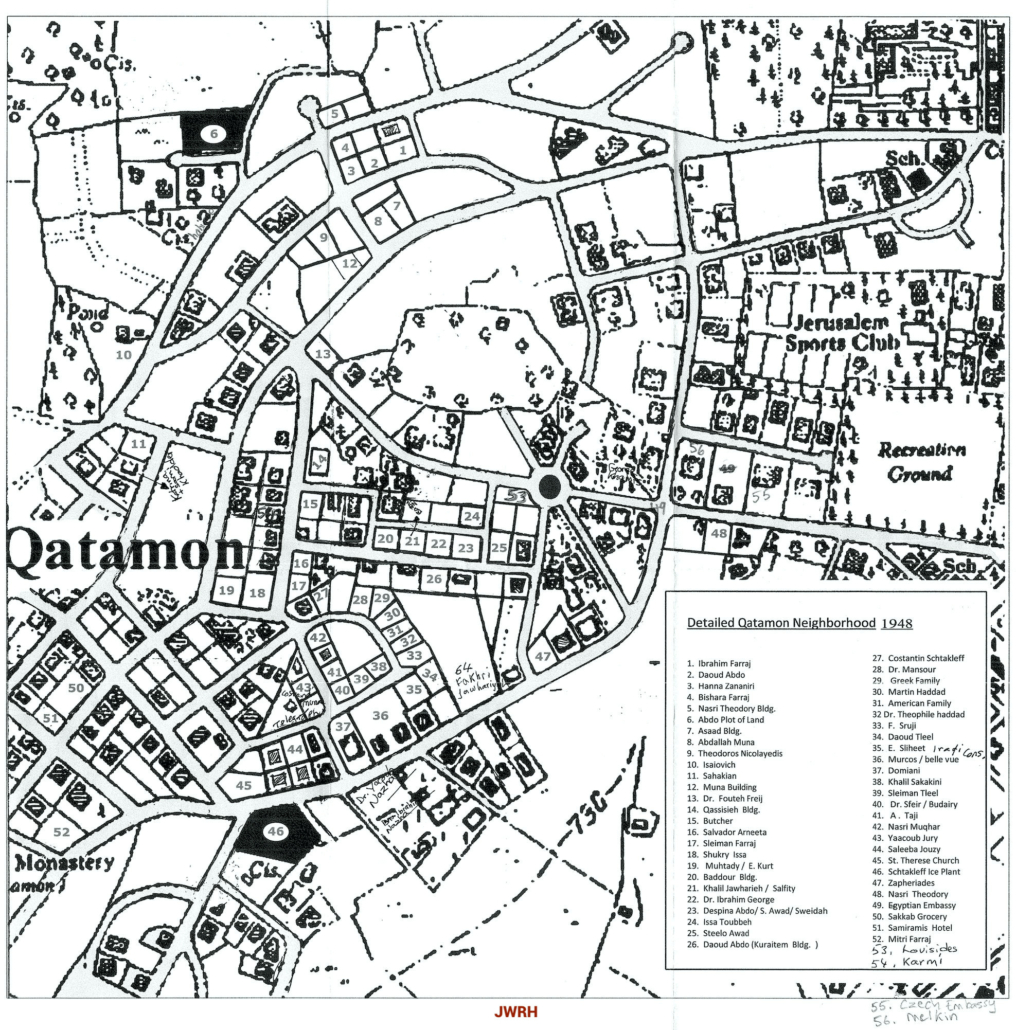

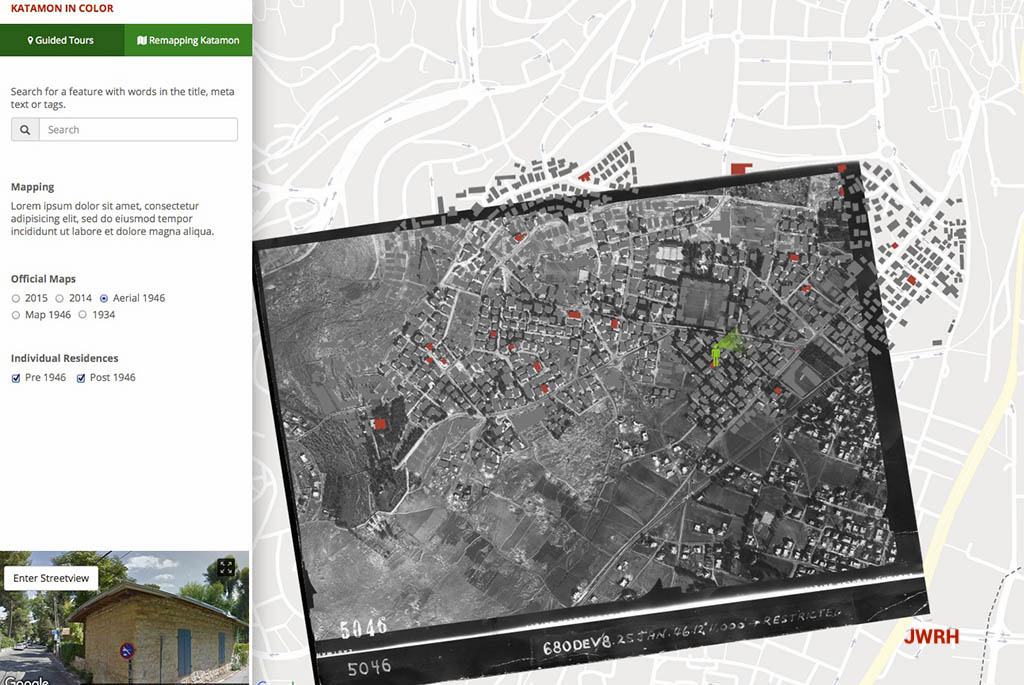

The process of developing the platform and finalising its look and functionality took about a year. Using a 1946 aerial photograph taken by the British as well as older planning maps dating to 1934 and 1938, buildings that existed up to 1948 were marked in dark grey. Later buildings are in light grey. When data is added to a dark grey entry, it turns red.

In the course of that year, the project also changed names. Having developed from a proposed in situ installation to a project heavily based on maps, its working title “Katamon in Colour” no longer seemed relevant. Jerusalem, We Are Here, with its nod to a place marker, also anticipated the expansions that were to come.

~ Drafts of “Katamon in Colour” ~

Once the platform was up and running, and before JWRH made its debut, we all got down to work. In November 2015, Dorit started entering test data. It was an exciting day when she emailed us a link to the Sakakini house where she had posted three photographs. In February 2016, with the look and feel of the project approaching its final form, I did my own testing, adding my grandfather’s house, along with others of friends and relatives. Mona then started transferring her “pins” to our map and continued adding information to other houses, making this communal map the new home for her research. The map generated its own momentum. We were all eager to identify more houses, make more connections, record more stories—and turn more grey houses red.

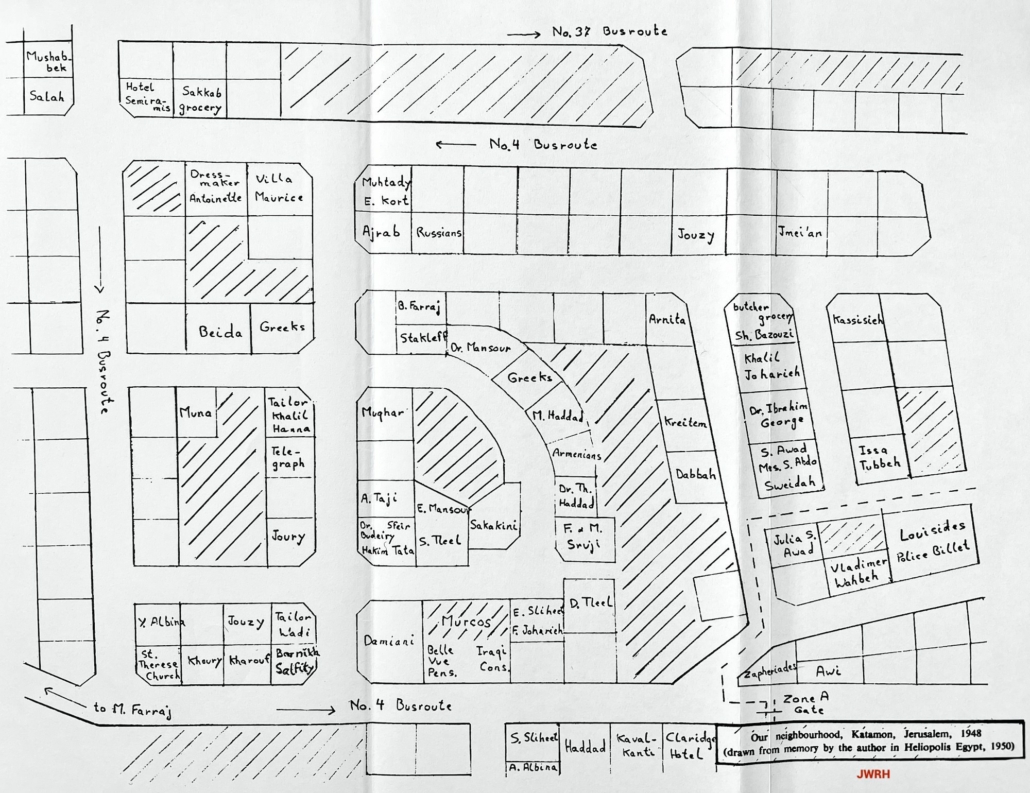

Some of the first entries were based on the map Hala Sakakini had hand-drawn and included in her memoir, Jerusalem and I, A Personal Record (first published in 1987). More came from a map included in the unpublished memoir of another Katamonian: Saba Abdo.

Significant input came from some of the project’s participants and collaborators. In the spring of 2015, Dorit met Nahil Aweidah in the streets of Katamon. Nahil was also doing research—for a book on her childhood. The two walked together in the neighbourhood and Nahil identified many houses. She also became one of the project’s participants. (See Aweidah on the Green tour.) Anwar Ben Badis, who conducts the Arabic tours on JWRH, also identified a great many houses, based on the information he has gathered through years of carrying out research and leading tours in the area.

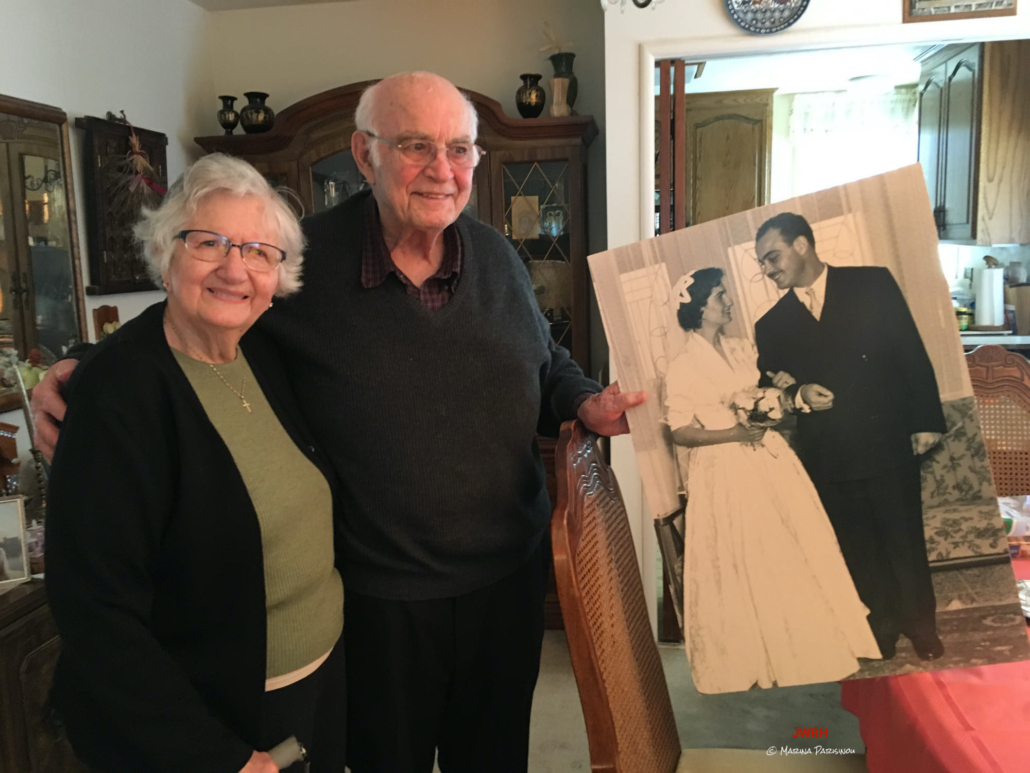

Interviews with Emile Jouzy, who lived as a boy with his family in Katamon and still remembers those years vividly, yielded a long list of houses. Then Mona showed the map to Laila and Issa Mashy who live in the San Francisco Bay Area and are a fount of information about Jerusalem and its people. Laila (née Muna) lived as a child with her family in Katamon and Issa in the German Colony. They are practically related to everyone (and to each other by blood, as well as by marriage). To this day, the Mashys are the go-to people for Mona and myself for any questions we have, and they keep adding to our knowledge. They contributed a great deal to the map—and continue to do so.

San Francisco Bay Area, Calif. – May 2017 (Photo by Marina Parisinou)

The information was not always accurate. Memory alters the perception of time and space; approximations and misinformation are inevitable. Before long, we found ourselves stepping on each other’s toes with conflicting information.

With my technical background as a database manager (in a previous life), I saw the map as a live database in need of management through standards and procedures. As a first step, I suggested to Dorit and Mona that we add our initials to the entries we each work on so that we know with whom to discuss additions or changes to the existing information of a building. I also proposed that we quote our sources for what we write and post (text, images, videos, etc). That way, not only would our work be more professional, but we’d also be better positioned to evaluate conflicting pieces of information and make decisions as to which piece should carry more weight. As an example, potentially—but not necessarily—a direct descendant of a family would be a more credible source than, say, someone who lived in the area and had only heard of the family. (“A So-and-So family lived at the bottom of the street.” “No, I visited the area with my father and he showed me his house. It was the one next to the one you’ve marked.”)

Later on, after the project was opened to the public, the issue was magnified following an instance or two where information about a house was changed substantially or its identification was completely overturned by new data. Oral history is by its nature fallible, subject as it is to the shortcomings of memory and the distortions of hearsay.

When one instance of oral history encounters another, how do you determine which one is the correct one, or the more correct one? Does the less correct one still contain accurate elements which the winning version did not include?

When Dorit and I discussed the issue, we both felt that we couldn’t simply replace information when newer data came in for the same entry, ie we could not be deleting data. So I introduced the Change Log which allows us to make changes without losing older data that may later be proven valid. We update the entry based on what we believe is the most accurate information on hand, but note the changes that were made, at the bottom, as a backup, thus tracking the history of updates and ensuring that no information is ever lost.

The project premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival (RIDM) in Montreal, on 12 November 2016. It didn’t take long for people to start contacting us about the map and sending us information and photographs. Each building has an email link that reads: “If you have any images, videos or even just information about this house, please send them to us.”

A search function allows the viewer to retrieve information by the tags we add to the entries or the names that appear in the title of each building. Tags help group entries by type of building (hotel, factory), by the profession of the residents (doctor, lawyer), by ethnicity (Armenians, Greeks), by source, etc.

The map, which in addition to Katamon included the Greek and German Colonies, sported more and more red as the months went by. But we soon found its borders confining. We had lots of information about people and places in other neighbourhoods of what today is known as “West” Jerusalem, like Baq’a and Talbiyeh, which were not included in the map. So, in May 2017, we decided to expand the map. To reduce the cost of this expansion, Helios added the buildings from a Google map and left it up to us to identify them as pre- or post-1948 (light or dark grey).

We also renamed Remapping Katamon—the green button that leads from the tours to the map. We wondered if it should say Remapping Southern Jerusalem but opted for the simpler—and, as it turns out, prescient—Remapping Jerusalem.

Connections on the Map

More area covered translated to more activity, more connections. The map has become a resource for many people and in turn has benefited from the same people and others.

In mid-2017, both Mona and I were contacted by Shaya Roth, a conservation architect from Jerusalem. He had deciphered the initials on the map and contacted each of us separately about entries we had worked on, requesting more information about houses on which he was preparing reports. He returned the favour by offering substantial information about other houses. Shaya not only has professional expertise and access to archives, but he is also passionate about Jerusalem’s history and its old houses; he also has an appreciation for the intimate connection people have with places they call home. Through the years, he has become a regular contributor, to the point where I now think of him—presumptuously, perhaps—as a collaborator on this project. He has been an invaluable resource and we often contact him with requests, taking advantage of his kindness and generosity. Our map is much richer thanks to him.

JWRH’s researcher Ilan Shtayer regularly sends us information he encounters in the British Mandate archives which have remained in Israel. We can often deduce information from seemingly unrelated files. For example, in various applications for building permits, alterations, and the like, the borders of the property are often defined by the names of the owners of the properties to the north, south, east, and west of the one in question, thus yielding valuable clues.

So data keeps coming in. But every so often, the process works in reverse. Rather than being sent information about a house, we are sometimes asked to find someone’s house. A case in point is that of the Cotran family.

In April 2017, Karena Batstone sent us a message from the UK via our Facebook page: “Hello, fantastic site”, she wrote. “My mother’s family lived in Upper Baq’a. They were the Cotran family—Michel, Hassiba, and their children, Ola, Omeir, and Eugene. They lived here,” she said, in reference to the photo she attached, and continued: “I went to Jerusalem trying to find it (we have no address) but wasn’t successful. Can you help identify?”

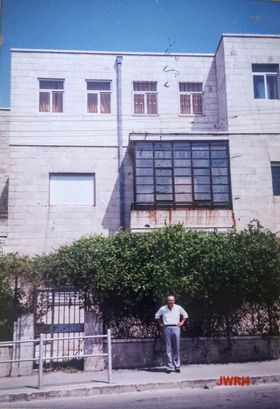

The man in the photo is Karena’s uncle Eugene Cotran (1938-2014) who “was a circuit judge in England and one of the main jurists in charge of the drafting of the Basic Law of Palestine.” (Wikipedia) He had visited the area some fifteen years prior.

I asked Karena if she could provide any clues she may have picked up from family stories that would help us narrow down the location. Was the house close to some known building or the railway lines? Did she know names of neighbours? She replied that the family rented from the Bahu family who owned busses; next to the house was a big yard full of busses. I sent this information to Mona asking for her input. Sure enough, a former colleague of hers at the Ramallah Friends School, Renée Sansur, is married to George Bahu, son of the bus company owner. Mona contacted Renée who sent her a photo that helped Mona identify the house on the map. And thus the Cotran family were able to find their house; they also received an invitation from George Bahu to take the family to see the house next time they visited Jerusalem. Karena reported that her uncle Omeir was thrilled with our findings. He has since been in regular contact with his old friend George.

The map connects people with their lost homes, and in some cases even with documents and photos that the family didn’t have. Sometimes that is the result of serendipity. On 13 April 2017, Dorit presented JWRH at the Jerusalem Fund, in Washington, DC. She was accompanied in her presentation by Jamil Toubbeh who flew from Arizona especially. As she hovered over some houses in search of the one in which Jamil was interested, she noticed two women in the audience whose eyes were filled with tears. She approached them afterwards and they told her that they had visited Katamon multiple times but had never been able to locate their family’s house even though their father had provided directions and descriptions. They saw it for the first time on the JWHR map where it had been identified through planning documents that Ilan had obtained a few years earlier.

Map vs Tours

And then there was the time when the map clashed head-on with the tours. In September 2021, Emile Jouzy and I were on a Zoom call preparing for his PES presentation (more about the PES in the next section). He was explaining that his family used to rent in a building not far from the Schtakleff ice factory but that his father also owned a villa in Talbiyeh which, for one reason or another, they never got to live in. So we pulled up the JWRH map to scope out the area. As we were (virtually) approaching southern Talbiyeh, in Google street view, we stopped at a fork of what today is called Tsvi Graetz Street and I panned around the area. Suddenly Emile cried out: “There, there! Go back! It’s that one!” Instant recognition.

However, what he had identified with such certainty as their family villa, both our map but also, more importantly, the tours listed as the Stephan house. It was in fact the first stop on the Yellow tour. But Emile was insistent. I said I’d talk to Dorit to see how it could be resolved.

To complicate matters even further, Mona had added a note in that entry identifying Mohammed Daoud Taher Dajani Daoudi as the owner, based on his daughter Abla’s identification.

Early on in the process of identifying houses, we had stumbled on the issue of owner versus tenant. We’d be looking for a house someone had lived in and in the archives we’d find paperwork listing someone else as the actual owner. There were of course many rentals in the area. And although the Stephan family were indeed renting, this was an entirely different case. For starters, Emile knew who his family had rented to and they weren’t the Stephans. And also Stepho Stephan, in his interviews, had mentioned the name of their landlord and it wasn’t Jouzy. Now we additionally had two people contesting the ownership of this building.

Dorit had always harboured some doubts about the exact location of the Stephan house. Stepho had mentioned that their house was very close to the Semiramis hotel. But the Semiramis was near the westernmost end of Katamon whereas this location is at its easternmost end, at the edge of Talbiyeh and the German Colony. Also he had identified the house based on information by a niece who had visited the area. Sadly, Stepho was no longer on this earth to be consulted.

It was one person’s word against another’s and another’s. Emile was understandably pushing us to recognise the house as his family’s but we weren’t ready to “evict” the Stephans without some concrete evidence. One Nakba had been enough; we didn’t want to subject the family to a second, albeit virtual, one. So the issue dragged on.

All good things come to those who wait—or so goes the popular saying. In February 2022, Ilan discovered in the archives a document showing that in 1932 the house had indeed been sold to Saliba Jouzy (Emile’s father) by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate. We were all thrilled for Emile—and for being able to make a clear call.

But with the house being part of the tours, a simple note in the Change Log was not sufficient to resolve the issue. The Stephans had to be moved to a place where they could still be part of the Yellow tour. After much discussion with Dorit and Helios, and with the consent of the Stephan family, we decided to relocate the Stephan house on an empty plot opposite the Jouzy villa. That way, the tour didn’t have to be drastically altered and Emile could “take possession” of his family’s house.

The Tony Mansour Map Expansion

Early in 2022, both Mona and I once again found ourselves wanting to add information to houses that were not on the map. Somehow, north Talbiyeh had been missed in the expansion of 2017. I raised the issue with Dorit and we decided to get a quote from Helios about that area and also about Mamilla so we could add important landmarks like the King David Hotel and the YMCA. The cost was doable—but not trivial—so Dorit set about obtaining the corresponding aerial maps from the Israeli archives.

In the meantime, in a case of project cross-pollination:

In an essay Dorit, Mona, and I co-wrote for the Jerusalem Quarterly in May 2022, we talked about how JWRH has spawned a number of other projects, like Mona’s Facebook page (British Mandate Jerusalemites Photo Library) and my blog (MyPalestinianStory.com). Another one is the Palestine Ethnographic Society (PES), a group that Mona and I have been running monthly since January 2018, which has evolved into an oral history project. We invite older Palestinians or descendants of Palestinians to talk to us about theirs and their families’ lives in pre-Nakba Palestine. We make a point of avoiding politics and focus instead on society and culture—hence the name Ethnographic.

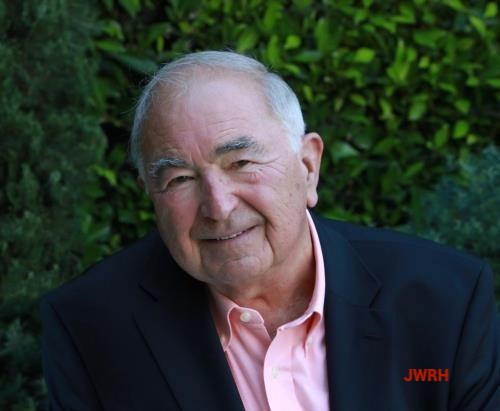

In November 2021, our speaker was Tony Mansour. His family is one of only fourteen who enjoy the privilege of carrying a banner during the Holy Fire ceremony at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Tony’s father, Elias, was born and raised in the old city of Jerusalem, in a house that has been in the family for hundreds of years to this day. Elias migrated to Honduras at the age of 16, went back to Jerusalem to marry, and then returned with his wife, Marguerite Hanania, to Latin America. He did well in Honduras but his wife longed for home. So they returned to Jerusalem with their two daughters and with Marguerite three-months pregnant. Tony was born a few months later, in November 1937.

(Tony Mansour archive)

The family first lived in Upper Baq’a. Elias started a new business: an automated bakery (thus becoming a competitor to my Schtakleff relatives) and moved his family to Mekor Chaim which was close to his Beit Safafa plant. The bakery was successful and Tony had fond memories of spending time there as a child. By 1947 a family home was under construction in Talbiyeh, on land Elias purchased from Abdullah and Hanna Muna. In the meantime, however, the situation in Jerusalem had deteriorated and Elias felt that his family was no longer safe in Mekor Chaim. They moved to a flat in Katamon, behind the Iraqi Consulate, next to the Sakakini house. That was to be their last home in Jerusalem. After the Deir Yassin massacre in April 1948, they fled to Jordan and from there moved to Lebanon.

(Tony Mansour archive)

Tony had been unwell at the time of his PES presentation so he had his son Anthony read his talk, conserving his own energy for the Q&A session. It was an eloquent talk—one of the best we’ve had to date—and everyone loved it.

Tony was taken by our group, too. A couple of months later, he emailed Mona and myself telling us that he loved what we were doing at the PES, despite the fact that his health did not allow him to participate regularly. He offered us a financial contribution towards our expenses and urged us to expand the group and include younger generations. We were both greatly touched. But the PES is a no-cost operation, running on my personal Zoom account—that’s the only expense. So I proposed that we use the money for JWRH, to fund the Talbiyeh/Mamilla expansion. In effect it’s not really that different a project. It’s still about oral history—like all our projects—and it’s still us (with a few other like-minded people). Only the medium is different. So I wrote to Tony, explaining our conundrum and offering to show him JWRH over Zoom. He readily accepted: “… my family will be honored to participate in this.”

In mid-March 2022, Mona and I met Tony on Zoom again. This time he was accompanied by another son, Jack. I shared my screen and gave them a tour: highlights from the walking tours, then the map, and finally our informational website. He appeared to be greatly moved and we started discussing the project’s needs. I explained about our recent quote from Helios and suggested that we could apply his contribution towards it which would leave only a small amount to be covered by us. He didn’t let me finish. “Stop! Stop!” he said. “Here’s my son Jack. He’s responsible for the family’s finances. He’ll make sure that you can draw for this project…” —and named a financial contribution significantly higher than the initial one.

My jaw dropped and tears came to my eyes. It wasn’t only the unstinting generosity but also the unequivocal validation of our work that moved me so deeply. Mona was equally astounded and touched. We didn’t know how to thank him.

I emailed a few weeks later to thank him again and introduce him to Dorit who was also overwhelmed by this incredibly generous gesture. I explained that we wanted to use the funds to complete the map of Jerusalem and “populate” the remaining pre-1948 buildings. He replied: “Thank you. It was very impressive. I enjoyed every bit of the pictures, the video and the special segment Ranwa did about Stepho [the above-mentioned Stepho Stephan] who was not only related to me, but my good friend since youth. I’m still willing to do whatever is needed. Please let me know. It will be my pleasure.”

It took us another month to get ourselves organised and get back to Tony. We all had our hands full with all sorts of other things in addition to JWRH. Dorit is a full professor at Queen’s University and working on another collaborative project; Mona had been working furiously on another book; and I was busy co-editing the content of the May issue of This Week in Palestine which was dedicated to Jerusalem. I emailed Tony with the latest Helios quote and asked about how to move forward. I did not receive a reply.

In mid-June 2022, Mona emailed me the sad news: Tony left this world on 5 June 2022.

With a heavy heart, I emailed Jack and Anthony my condolences. I hadn’t known Tony very well but my limited contacts with him had made a big impression, and not only because of his generosity. His story, which he was so diligent in preserving, is that of so many Jerusalemites’, including my own family’s. I feel strongly that as we lose each member of that generation, we lose something most valuable. I’m glad that Tony’s story will live on in the video recording of our PES session and in his own book.

Jack acknowledged my message immediately, and despite the difficult time he and his family were going through, assured me that they had every intention of honouring their father’s pledge to JWHR in order to “keep his memory alive with this project.”

So we have been moving forward—albeit in fits and starts, as life keeps getting in the way. We have decided to use the entire amount offered to expand the map, rather than use some of it for running expenses. That way the family can identify with a concrete part of the project and Tony Mansour’s name can be directly linked to it.

In May 2022, Helios deployed the map extension we had requested—north Talbiyeh and Mamilla—and sometime later I started working on populating some key entries: the King David Hotel, the YMCA, and the Palace Hotel.

The following month, Dorit and I had a Zoom call to figure out how the additional aerial photographs she had purchased fit on the map. She then built a slideshow as a guide for Helios on how to position them.

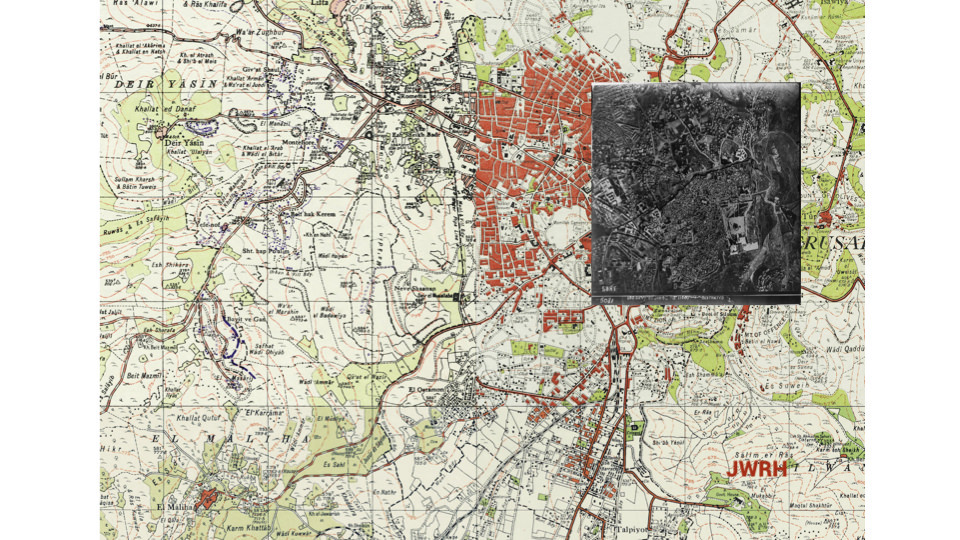

In the meantime, I had shared with Dorit a map that was sent to me by Alvaro Gomez Pidal. A filmmaker from Madrid, Alvaro is one of my two Semiramis research buddies and is indeed the person to whom I owe my Semiramis journey (more on my blog.) He had stitched together four maps from the Survey of Palestine, creating what in Spanish he called a supermapa (a name we’ve adopted). We thought it would be a great addition to our map. The overlays we had up until then were either aerial photos or property maps. The supermapa covers the entire Jerusalem and shows more than just plots. It includes contour lines showing elevation, cultivated areas, and a host of other details. Alvaro was happy for us to use it—for which we thank him.

The dates listed on the map range from 1933 to 1942. We thought that areas such as the Greek Colony looked too sparsely built so we chose to label this overlay 1933. We can revisit that decision if and when we have a more accurate estimate about the date of the buildings which is what our project focuses on (as opposed to the roads which on the map were revised in 1942).

As we discussed the expansion with Helios, we became aware of the limitations of the map’s infrastructure. Digital projects are not immune to the effects of age. The codebase on which the entire project is built is about nine years old, rendering it practically obsolete. It can continue to run as is for a long time, but the scope of changes is very limited. We could not add another layer to the map because the current header didn’t have enough room to accommodate it.

Helios gave us two options. The first was a band-aid: substitute the supermapa for one of the other map overlays. The ideal solution would be to future-proof the site by using WordPress for content management. However, the cost for the latter would be in the region of $25K. So we shelved that option, hoping that the current expansion will open up our project to a broader audience and perhaps to more offers for financial support, which would make the infrastructure upgrade possible. We opted instead for the band-aid option: the supermapa replaced the 1918 aerial photograph on the map.

With those updates now in place—the new aerials, the supermapa, and the north Talbiyeh and Mamilla extensions—we are currently in the process of slicing up the rest of Jerusalem into small sections for which we will ask Helios for individual quotes. We will then prioritise their deployment weighing their importance and cost. We are confident that what remains of our funding can take us a long way—if not all the way—to completing Palestinian Jerusalem outside the walls.

We look forward to adding to our map stories of people who lived farther afield than west Jerusalem—stories from Musrara, from Rehavia, from Romema, and even from Sheikh Jarrah.

And for all this we are deeply grateful to Tony Mansour and his family, in particular his three sons: Anthony, Jack, and Louie Mansour. Thank you!

(20 Nov 1937-5 Jun 2022)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!